The HABS archives online at the Library of Congress are easy to search -- I looked for Shaker Stove / Oven / Kitchen /Room in compiling this selection. But there are almost too many hits, and the pictures, while eloquent in their own way, lack commentary and organization. So I will provide both, trying not just to repeat what's in my Shaker Stoves essay, to which I refer any readers who come across this, as well the other two Shaker Stoves blog postings: the original Shaker (or "Shaker") Stoves and the recent Shaker Stoves on US Auction Sites.

HABS complements those earlier postings because its strengths lie in different areas than theirs -- stoves in situ rather than as de-contextualized art objects; and stoves other than the small room heaters that were the most numerous type of Shaker stoves, and that understandably dominate museum and private holdings. But I'll start with a few pictures where the stove is the centre of attention, as it always is in the other couple of postings. I include good-quality JPEG versions of the images, but the links will take you to the Library of Congress site, where you can also get very good TIFF versions.

- Fig. #1: Theodore Webb, Photographer, DETAIL OF HEATING STOVE -- Shaker Centre Family Dwelling House, Shakertown, Mercer County, KY, Feb. 2, 1934. HABS KY,84-SHAKT,1--9

This is a "super-heater" or "double-decker," a modification of the standard or smaller Shaker heating stove designed to increase its output by adding to the radiating surface area and transferring more heat out of the flue gases and into the room before they escaped up the chimney. The stove has "worldly" cabriole legs rather than the more usual Shaker peg legs, probably because the Western Shakers got all of their casting done for them by commercial foundries. It is evidently just set out for display purposes against a wall, and neither in use nor even capable of being used: it was in quite poor condition, probably after years of neglect, but if it had been fired up so close to a wooden floor and wainscotting, it would have been a big fire hazard.

Here's another version of the same design, sitting on a board to protect the linoleum floor, and with the flue exiting at the front of the upper chamber, not the back:

A nice picture of a very simple, quite wide and boxy stove. Something to note about this image is its date: by the 1960s, Hancock and other villages were becoming quite museumified, a process which involved more than just conservation of what was there, but editing out of objects that did not fit and conscious recreation of what experts thought of as the classic, uniform style of the ante-bellum Shaker "Golden Age." Photographs from the 1930s show a much messier and mixed-up style then still surviving from the last decades of villages' times as live, if shrinking, communities. By the 1960s, that reality had been replaced by what museums' creators thought of as a better as well as a truer version of the stripped-down Shaker style that they idealized.

- Fig. #4: Jack E. Boucher, INTERIOR OF ELDERS' ROOM, SHOWING SHAKER FURNITURE AND STOVE -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, June 1962. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--32

This is a distinctive and quite early style of Hancock stove, its box fairly high relative to its lengthg and width, and with a five-sided rather than round front hearth, visible also below. This room is a set -- a display space for classic Shaker wooden furniture.

- Fig. #5: Jack E. Boucher, INTERIOR VIEW, SHOWING TYPICAL SHAKER IRON STOVE, TABLE -- Shaker Ministry's Washhouse, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, June 1962. HABS MASS,2-HANC,18--4. There is a recent colour picture of this room and stove on Flickr -- it looks as if the walls could do with a fresh coat of paint.

Whatever the caption may suggest, this is not a "typical" Shaker stove, it's actually a very interesting and early one -- basically an iron fireplace (a sort of "Franklin") rather than a stove, broader than it was deep and made to take a log widthways rather than lengthwise. It doesn't have a proper door, but rather a wrought-iron top-hinged "blower" to speed the ignition of kindling. Most of the time, this stove would have burned with the blower propped open, and a nice clear view of the fire. The shape is significant, too: a truncated pyramid on top of the plain trapezoid that became the Shaker norm -- another indication of this stove's early date. The (short) legs are wrougght iron with penny feet, common on other early Shaker stoves.

- Fig. #6: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, INTERIOR SHOWING TYPICAL SHAKER FURNITURE AND HEATING STOVE -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, 1931. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--35

What is interesting about this image by William Winter, one of the earliest and most important of the photographers who recorded Shaker material culture and architecture, is that the stove, sitting on its metal stove-board, is almost the only object about whose place in this room one can be confident. The other bits of wooden furniture have just been brought together for the picture. Winter did plenty of this sort of set-dressing, at first rather naively, as in this picture, but increasingly self-consciously, with the intent of enhancing or even creating a sense of "the" classic Shaker aesthetic of the kind that one can see in its mature form in Jack Boucher's Hancock images from the early 1960s.

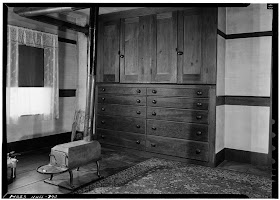

- Fig. #7: Jack E. Boucher, INTERIOR SHOWING CABINETS AND IRON STOVE -- Shaker South Family Shop No. 1, Harvard, Worcester County, MA, August 1963. HABS MASS,14-HARV,15--2

What is interesting about this Boucher image, from one of the three smaller communities in Massachusetts rather than the larger, longer-lived, and much more photographed and visited Hancock, is the type of stove: an early, transitional truncated-pyramid-on-trapezoid shape, with very worldly cast-iron cabriole legs. Harvard, like the western settlements, did not have its own foundry, so presumably had this made for them. Similar stoves were found in Hancock, Enfield, New Hampshire, and probably elsewhere too -- for illustrations, see the other two Shaker Stoves posts, and Fig. #12, below. This room is not as stripped-down and dressed up as in Boucher's pictures of Hancock, probably because Harvard's properties remain in private ownership.

Fig. #8: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, BUILT-IN CABINET, STOVE, AND A SHOVEL FOR TRANSFERRING LIVE COALS -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, December 26, 1939. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--36

The significance of this image is that it is of a late-model stove, manufactured to Shaker designs but years after they had given up making their own stoves. This stove is a plain six-plate box with cabriole legs rather like the ones in the previous image. The distinctively Shaker aspect of its design, apart from its relative plainness, is the hinged flap in the top plate of the stove, half-concealed by the ash-shovel. This was used for putting in fuel, including awkward chunks of wood that would not fit easily through the door. The sliding hatch in the front hearth was used to control the draught. This style of stove probably originated in Canterbury, New Hampshire, some time between 1840 and 1870. It displaced the older trapezoid stoves from Canterbury so completely that when the village was turned into a museum in the 1990s, after the last eldress died, the museum director, Scott Swank, had to buy "classic" Shaker stoves from antique shops in order to be able to decorate some rooms in the early C19th style that visitors would expect to encounter. Canterbury Shakers had got rid of the classic Shaker stoves they had made for themselves, because they thought these new ones, which they had made for them at a nearby commercial foundry, worked much better. Perhaps the best picture of one of these stoves that I have seen -- and possibly of a larger model -- is from Canterbury itself, and on Flickr.

This picture, even more than Baldwin's, Fig. #8 above, shows how Shakers actually lived and heated (some of) the private rooms in their dwelling houses by the late nineteenth century -- in a style blending Shaker-made heirloom furniture with commercial goods reflecting a partial acceptance of Victorian taste, and a greater emphasis on comfort. The stove in the middle of the room is a "Rosedale," manufactured by the firm of John S. & Merritt Peckham of Utica, NY from at least the mid-1880s. Watervliet, the oldest Shaker settlement, had never had its own foundry, but had once used stoves and other appliances made to Shaker designs and specifications.

Fig. #10: J.S. & M. Peckham, Utica, NY, "Rosedale" Trade Card, n.d. -- and, for the specifications, the back of the card.

Fig. #11: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, SISTER'S ROOM -- Shaker South Family Dwelling House (second), New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, 1920's HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,17--7

We can see some of the same changes in William Winter's slightly earlier photo of a sister's room at New Lebanon, the second and much larger Shaker village in New York State. As with Winter's other photographs, we cannot be confident that the three items of wooden furniture lined up in a row have not just been brought into the room to decorate it. But we can trust the wallpaper, the oilcloth or linoleum on the floor, and the picture on the wall, as well as the stove -- made to a design more than a century old, and still serviceable, though this does not mean that the stove itself was anything like that ancient. They remained in production, essentially unchanged, for decades. (Q: Was the iron-doored receptacle behind the stove, which had dirtied the wallpaper above it, for the storage of firewood or for the disposal of ashes? Probably the latter, I think, though I have read both explanations for its purpose.)

Finally, one of the most arresting images testifying to Shakers' acceptance of new domestic technologies in the interests of greater comfort, convenience, and economy, comes from the North Family at New Lebanon, who had installed steam heating in their dwelling house as early as the 1860s:

Fig. #11a: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, RADIATOR AND STOVE -- Shaker North Family Dwelling House (second), New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, December 1939, HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,28--10

Here, as in other late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century Shaker interiors, the old and the new, the home-made and the bought, lived amicably enough side by side.

* * *

Here, for example, is a picture of one of the Brethren's [work] Shops at Hancock, with a centrally located Enfield-style stove.

Fig. #12: Jack E. Boucher, EAST PORTION OF FIRST FLOOR, SHOWING HEATING STOVE - - Shaker Church Family Brethren's Shop, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, June 1962. HABS MASS,2-HANC,1--8.

Shaker work and workplaces were very gender-segregated, and there seem to be far more images of the women's spaces than of the men's. Cooking, washing, ironing, mending and making clothes -- these, as well as cleaning, and indeed bringing up children (though not biologically their own), were the principal women's occupations in Shaker families just as much as in other 19th-century households, and they all had their distinctive communal work sites, with appropriate styles of stove to supply either space or process heat.

- Fig. #13: W.F. Winter, Photographer, SEWING ROOM -- Shaker South Family Sisters' Workshop, Watervliet , Albany County, NY, Summer 1930, HABS NY,1-COL,17--1

This is a picture with, though not of, the same super-heater shown in close-up in Figure #2, above. It shows the stove's context -- in the alcove of a sewing room where the South Family's Sisters at first made, and later mostly just repaired, the community's clothing and other textile goods. The stove is not just to warm the work space, whose size explains the need for a super-heater rather than just one of the smaller heating stoves appropriate to a "retiring room." It is also a tool for the Shaker tailoresses -- used to heat flat irons for pressing clothes. There is another nice Flickr photo of a sewing room at Hancock that shows a single-decker stove with a recess in its top, also used for heating irons.

A family of up to a hundred Shakers produced an awful lot of washing and ironing, so it is understandable that Shaker laundries were built on a large scale, and had their own distinctive types of stove. (Distinctive, but not unique -- laundry and ironing stoves were regular features in commercial stove makers' catalogues too.)

The best picture I have seen of one of the Shakers' powered laundries -- a technology they had developed in the mid-nineteenth century -- is also one of the oldest in the HABS collection. The only "stove" visible in this case is an enormous conical water-heater. Note that, even in 1930, it was still wood-fueled.

Fig. #14: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, LAUNDRY ROOM, Shaker Church Family Sisters' Workshop, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, May 1930. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,11--3

Winter also took pictures of the New Lebanon Church Family's ironing room when it was still in use:

Fig. #15: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer. IRONING ROOM, Shaker Church Family Sisters' Workshop, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, 1920s. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,11--4.

Notice the drying lines, to make use of the warm atmosphere, and the box-like sheet-metal cover on top of the small heating stove on the right of this picture. It was probably designed to speed up the heating of irons underneath it; for larger jobs, the huge conical stove in the background would serve. Winter was sufficiently interested in this apparent prototype for a Project Mercury space capsule that he took two pictures of it, one with its doors closed (showing their elegant wrought-iron latches) and the other with them open, to show the racks of irons inside.

Fig. #16: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, IRONING STOVE IN LAUNDRY ROOM, Shaker Church Family Sisters' Workshop, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, Summer 1931. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,11--10

Fig. #17: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, IRONING STOVE IN LAUNDRY ROOM, Shaker Church Family Sisters' Workshop, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, Summer 1931. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,11--9

Thirty years later Jack Boucher made his own set of images of nearby Hancock's very similar installation:

Fig. #14: Jack E. Boucher, FIRST FLOOR, WEST END SHOWING FLATIRON HEATING STOVE -- Shaker Church Family Washhouse & Machine Shop, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, June 1962. HABS MASS,2-HANC,14--13.

We can see a brick-set copper or iron wash boiler against the wall, with a conical ironing stove (a sheet metal enclosure around a firepot) and a double-decker waiting to be refitted into the room -- for the room as now restored, see this 2006 photo on Flickr. Boucher was sufficiently interested in the ironing stove that he also took a detail view, apparently before restoration began:

Fig. #15: Jack E. Boucher, FLATIRON HEATING STOVE -- Shaker Church Family Washhouse & Machine Shop, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, June 1962. HABS MASS,2-HANC,14--14.

This was perhaps the most impressive type of ironing stove, but not the only one. Two more were recorded from the same building in the 1930s:

Fig. #16: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, IRONING STOVE -- Shaker Church Family Washhouse & Machine Shop, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, 1931. HABS MASS,2-HANC,14--15.

Fig. #17: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, CAST IRON STOVE -- Shaker Church Family Washhouse & Machine Shop, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, December 28, 1939. HABS MASS,2-HANC,14--17. There is another good picture of one of these stoves -- William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, IRONING ROOM -- Shaker South Family Washhouse, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, Summer 1930. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,20--9

A stove very like this one figures as a measured example in Ejner Handberg's Shop Drawings of Shaker Iron and Tinware (Stockbridge, MA: Berkshire Traveller Press, 1976), pp. 28-9, from which we find that it was 14" wide and 31" long (excluding the front hearth), standing 10.25" off the floor, and capable of heating irons on the slightly recessed top as well as along both sides. Many irons were needed for a big job of ironing, because they needed to be put back to heat up again quite frequently.

Fig. #18: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, BRICK STOVE FOR HEATING FLATIRONS -- Shaker Church Family Washhouse & Machine Shop, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, December 28, 1939. HABS MASS,2-HANC,14--16

* * *

Even more important than the laundry and ironing room in Shaker domestic economy was the kitchen. Here, too, we find large and quite distinctive stoves. Perhaps the oldest is in one of the rare survivors from the first (1790s) generation of purpose-built Shaker dwelling houses:

Fig. #19: Jack E. Boucher, BAKE OVEN, SOUTHEAST ROOM, BASEMENT-- Shaker Church Family Dwelling House (second), Harvard, Worcester County, MA. April 1963. HABS MASS,14-HARV,12--6

It is not possible to tell very much about this oven from the above image -- for example, how much of the original installation had survived? -- and the accompanying measured drawing is no help, but it looks as if it is a massive brick-built structure whose only ironwork is the door. A family with an oven like this would probably still have had to do most of its cooking in a conventional open-hearth fireplace.

By the time that Shakers were building their much larger second-generation dwelling houses, in the 1800s-1810s and after, they had gone beyond open-fire cookery and adopted versions of the most advanced installations for large-scale catering seen in the United States at that time -- notably "Rumford kitchens," with fixed iron boilers, ovens, and cooking hearths. The best surviving example of these -- at least, the most frequently photographed -- is at Hancock, and dates from 1830. When it was completed its designer, Elder William F. Deming, described its boilers proudly as "on a plan of my own invention, which proves to be the best ever see." There were also "two excellent ovens made on an improved plan which will bake four different settings at one heating," i.e. enough for the day's two main meals for the Family's hundred members.

Fig. #20: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, BRICK OVENS IN KITCHEN -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, December 28, 1939. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--14

The boilers can be seen quite plainly, either side of the main central stack of ovens, together with a circular "pie oven" in the end facing the camera. These appliances all had their own separate fires, so they could be used independently of one another, but they shared the same chimney stack. The massive brick chimney is reinforced against heat expansion and cracking with iron straps and bolts. In the background can be seen a big, later (from its plain style, probably early C20th) anthracite-fired kitchen range, which complemented and had probably largely replaced the original installation by Hancock's final decades, as its population declined.

The kitchen in Hancock's Brick Dwelling House has gone through several restorations during its subsequent life as a key attraction of a popular museum, traced in the following images:

Fig. #21: Jack E. Boucher, LARGE BAKE OVEN, BASEMENT FLOOR, SOUTH ROOM (OVEN HAS FOUR HEATS FROM CENTRAL FIRE) -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, June 1962. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--15. The arch kettles in the left-hand alcove of the brick chimney, and against the wall on the right-hand edge of the picture, have been removed. Boucher is probably wrong about the "four heats," given that there were separate fires.

Fig. #22: Elmer R. Pearson, Photographer, KITCHEN, GROUND LEVEL, LOOKING NORTHWEST -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, 1970. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--16

As we can see, the smaller boiler had been removed from the left-hand alcove to make room for a dough-kneading trough. Pearson's picture shows another large boiler on the right-hand side, concealed in Baldwin's and Boucher's images. The way they vent into the common chimney is clear in this third image. Pearson also took a different view of the restored kitchen, showing how the early 1900s range had been removed and replaced by a smaller, older wood-fired cooking stove which must have been thought more appropriate to the period being recreated:

Fig. #23: Elmer R. Pearson, Photographer. KITCHEN, GROUND LEVEL, LOOKING EAST -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, 1970. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--13

Moving forward to today, Hancock's original kitchen, with its numerous "arch kettles" for boiling water and heating food, seems to have been entirely restored, with even the early C19th kitchen stove removed:

Fig. #24: Angela ("Moonfever0"), IMG_4834, 29 June 2010, Hancock Shaker Village. The cooking stove in place by 1970, has been replaced by another arch kettle, also visible in Pearson's image, Fig. #23.

Fig. #25: Angela ("Moonfever0"), IMG_4836, 29 June 2010, Hancock Shaker Village. This small boiler and cooking hob is just visible behind the end wall in Pearson's image, Fig. #23.

No other Shaker kitchen seems to be as well documented as William Deming's Hancock masterpiece, but good images of key pieces of equipment at other villages are also available, so that we can see local variations as well as a common technological style.

Fig. #26: N.E. Baldwin, Photographer, ARCH KETTLE IN KITCHEN -- Shaker South Family Dwelling House, Watervliet , Albany County, NY, November 1939, HABS NY,1-COL,14--5

Fig. #27: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, KITCHEN -- Shaker South Family Dwelling House, Watervliet, Albany County, NY, Late 1920's or 1930's, HABS NY,1-COL,14--4

The interesting thing (for me, at least) about these two pictures is how Baldwin's close-up omits the crucial context that Winter's earlier long shot reveals -- that the old wood-fired boiler, its right-hand unit converted into the heater for what looks like a sheet-iron warming oven placed on top of the hot plate, is dwarfed by the massive and ornate late-nineteenth-century anthracite range (a "Kitchener" by Magee & Co. of Boston) that had replaced it. Watervliet's range, like Hancock's in Fig. #20, would have been more versatile, less labor-intensive, and more convenient -- heating, for example, a big vertical cylinder full of water at the same time as enabling all cooking operations to be done on the same appliance.

Another image of a kitchen at New Lebanon shows a new appliance (in this case, a Devonshire No. 24 range by the Richardson & Boynton Co. of New York and Chicago) had been installed in such a way as to displace all but one of the old arch kettles and, probably, make the old round pie oven as unusable as it was redundant.

Fig. #28: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, KITCHEN -- Shaker South Family Dwelling House (second), New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, Summer 1930. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,17--11

Shakers had different sorts of kitchen -- as well as those in the basements of their large dwelling houses for feeding whole families, separate production kitchens where they cooked and canned the high-quality food products they sold to the public.

Fig. #29: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, CANNING KITCHEN -- Shaker North Family, Dwelling House, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, November 1939. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,24--11. The bars on the front of the fire doors on two of the arch kettles are probably to protect cooks' legs from burns.

Fig. #30: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, CANNING KITCHEN SINK -- Shaker North Family, Dwelling House, Shaker Road, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, November 1939. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,24--12

One problem that Shakers had with large-scale food preparation in multi-storey dwelling houses was moving quantities of food between floors in an economical manner, and in a way that made sure that it didn't arrive cold. One solution can be seen in the New Lebanon cannon kitchen -- a "dumb waiter," or simple but effective elevator, powered by hand-turning a wooden windlass.

Fig. #31: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, CANNING KITCHEN ELEVATOR -- Shaker North Family, Dwelling House, Shaker Road, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, December 1939. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,24--13

Another solution is visible at Hancock: putting an old heating stove under a sheet-iron top to create a hot plate for keeping food warm between its arrival from the kitchen and its being served up in the next-door dining room:

Fig. #32: N. E. Baldwin, Photographer, STOVE, WOOD BOX, AND ENCLOSED SINK IN SERVING KITCHEN -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, December 26, 1939. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--17

Dining rooms were important communal spaces in Shaker dwelling houses, and also large enough to need their own heating solutions:

Fig. #33: Elmer R. Pearson, Photographer, DINING ROOM, SECOND FLOOR, LOOKING EAST -- Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, 1970. HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--30

Perhaps Hancock had always looked as plain and simple as in Elmer Pearson's austere image, a portrait of polished old wooden furniture and floors and a couple of classic heating stoves. Or perhaps this was a recreated version of the past, displacing the one that the last generations of Shakers had actually created for themselves by blending old and new technologies, Shaker-made and bought-in products. As the following picture from nearby New Lebanon shows, the Shaker stoves and benches had disappeared from a room now needing to accommodate just a handful of elderly residents, but probably doing so more comfortably thanks to a size 16 "Windsor" model, anthracite-fueled base burner, with patent "Ventiducts," instead. This stove probably dated from the turn of the century, like the ranges in Shaker kitchens, but these durable, ageing appliances were what the Shakers had come to depend on.

Fig. #34: William F. Winter, Jr., Photographer, DINING ROOM # 2 -- Shaker South Family Dwelling House (second), New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY, 1920's. HABS NY,11-NELEB.V,17--10. The stove is probably a Chicago Stove Works "Gold Coin"-brand Ventiduct Base Burner -- "The only Base Burner with Ventiduct Tubes correctly applied" so as to draw in cold air at floor level, heat it in the decorated iron jacket around the firepot, and expel it at the top, "thus heating the remote corners of the room by hot air circulation." It was, they claimed, "the only stove combining the advantages of a hot air furnace and a base burner." "SEE IT AND YOU WILL BUY IT." (Quotations from colored brochure, n.d., in the collections of the Rensselaer County Historical Society, Troy, NY, where Bussey & McLeod, founders of the firm that became the Chicago Stove Works, were based, and of which B. & M. continued as its Eastern Division until its closure in 1916.)

* * *

Finally, one kind of communal space was the heart of every Shaker community -- the Meeting House; and every dwelling house had its meeting rooms, for the Family to get together for week-night worship and sociable "union meetings," and for Sunday worship too, in the depths of winter when the large Meeting House was impossible to warm. All of these had stoves -- Meeting Houses were the first purpose-built Shaker structures, the oldest dating back to the early 1790s, and they were probably also the first to be stove-heated. The HABS archive holds numerous surveys of meeting houses, but few of the accompanying pictures include stoves. That of Sabbathday Lake, in Maine (built 1794, but with a mid- to late-nineteenth-century stove), is the best:

Fig. #35: Gerda Peterich, Photographer, MEETING ROOM, LEFT - Sabbathday Lake Shaker Community Meetinghouse, Cumberland County, ME, June 1962. HABS ME,3-SAB,1--4. There is also a close-up of the rather crude double-decker stove, and a picture of the single-decker on the other side of the room -- http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/me0005.photos.087966p/resource/, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/hhh.me0005.photos.087959p/.

Curiously, the best picture of a classic Shaker stove in a meeting house that I can find in the HABS archive is not in a Shaker community at all -- it's in the Flushing, New York, Quaker (Society of Friends) Meeting House. Why and how this old Hancock-style stove ended up there, 150 miles from Hancock, is presently a mystery.

Fig. #36: Society of Friends Meetinghouse, Flushing, Queens County, NY, HABS NY,41-FLUSH,1--20. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/hhh.ny0888.photos.122342p/ shows the stoves in context.

Meeting Rooms in dwelling houses are rather better served in the HABS archive. One of the best images is from Hancock:

Fig. #37: Jack E. Boucher, creator. LARGE ROOM (PROBABLY MEETING ROOM), NORTH END OF FIRST FLOOR - Shaker Church Family Main Dwelling House, Hancock, Berkshire County, MA, June 1962 . HABS MASS,2-HANC,4--19.

* * *

There are of course plenty of other good picture sources for Shaker villages and stoves online, notably via Flickr, but HABS's are very hard to beat -- for quality, systematic coverage, proper labelling, contextualization (with multiple images, measured drawings, and sometimes useful historical essays). HABS contains more stove images than I have thought it worthwhile including here -- I have given little attention to the western communities, for example -- but this is enough for now, and (I am sure) for most imaginable viewers who may stumble over this blog post, whether by accident or design.

I realize this is an old article. First--interesting and gorgeous photography! For such utilitarian things, they really are beautiful. Second, and the reason for my post, can you tell me more about the stove in Fig. 1? Is there a baffle in the upper chamber of the stove, so the smoke doesn't just shoot straight through and up the stack? Obviously for the other stove, with the pipe coming in the back and out the front, the smoke needs to travel the entire distance thereby heating the iron. Thanks for any info. Again, great writeup and photography.

ReplyDeleteGood evening Dr K., thanks for your kinds words. I like trying to write words that add a bit of context to illustrations like those. But as I haven't been to more than one Shaker village (Hancock, 1986) my knowledge of these objects is just through words and pictures, not from the physical things themselves. So I'm not sure I can answer your question. HOWEVER, I would be amazed if there was not a baffle inside the superheater in that first photo. I can see why it's made that way -- looks like a very elegant solution. And I will ask a guy who probably knows.

ReplyDelete