|

| Albany in the 1850s, showing busy river traffic and the Erie Canal entrance. |

The towns of Albany, Troy, and to a much lesser extent Schenectady were the most important centres of innovation, design, and production of American stoves in the industry's "Golden Age" between its emergence in the 1830s and its maturity after the Civil War. The Hart Cluett Museum in Troy and the Albany Institute of Art and New York State Museum in Albany have the finest public collections of its products. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy and the New York State Library in Albany hold the most voluminous company archives illuminating its inner workings. And the work of Tammis K. Groft at the Albany Institute did more than anybody else to draw the industry and its products to public attention in the exhibitions she organized forty years ago and with the catalogue Cast With Style: Nineteenth-Century Cast-Iron Stoves from the Albany Area (Albany: Albany Institute of History & Art, 1981, rev'd ed. 1984) that she wrote. This was what first introduced me to the stove industry and its forgotten importance a few years later.

I have written, and even formally (i.e. not just here or elsewhere online) published, plenty about the stove industry already using these local resources, but I've decided now to compile something that's long overdue: a guide to one crucial source for the early history of the industry that I have been developing for years, but that's been hard to share.

This is the record of inventive activity contained in U.S. patents for invention and design. In many cases the patent is the only primary source we have for knowing what products looked like, how they were made, how they were supposed to work, and what problems they were supposed to help makers and consumers solve. This is because examples of most of the stoves themselves have not survived until today, and few of the industry's hundreds of inventors, designers, entrepreneurs, and even companies left any archives at all.

Behind the patent itself, in the US National Archives, there may sit files of correspondence, particularly for the most commercially significant and heavily litigated ones, but online and in the public domain all we can find are the bare bones -- the patent drawings and explanatory text. To understand the evolution of the products, though, these are the most important sources.

They are easy to look at but quite difficult to find. This is because the most user-friendly interface with the USPTO's online holdings, Google Patents, can only -- and not always reliably -- locate patents that were printed by using a word search (e.g. for an inventor's name). This means that all early manuscript patents are even harder to discover, and impossible if you don't know their number. The USPTO's own search interface has no such limitations -- it can find everything that's there -- but not by a full-text search for any pre-1976 holdings (Google Patent will reach more than a century further back). So to find old stove patents, you also need to know their numbers. And where can you get those? Where is the key?

There is a key, and it was published almost 150 years ago -- a tabular compilation of the most important details of all US patents between 1790 and 1873, filling three fat, crammed volumes. All of this information was scanned and digitised a couple of decades ago by ProQuest and is readily available to anybody with access to a library holding a subscription. I used it to start building my own database in the early 2000s, and carry on improving it. But my database isn't easily shareable -- the key fields are easily translated into spreadsheet format, but the notes I have added that describe each patent don't fit. So the public key that I have provided is not as much use to any e.g. stove collector looking for a particular model as the private version of the database is for me.

So what I will do here is the same as I've done in several blog posts already, notably the last one on Ezra Ripley and Nicholas Vedder -- produce a catalog with an entry for every patent that gives the information needed to find it online, and also a (usually brief) description taken from my database that expands on what was provided in the 1873 volumes and will help any reader to decide whether it's worth following the link taking them to the original document in the USPTO files.

But there are so many New York Capital District stove patents -- 1,278 between 1810 and 1873, vs 5,752 from the rest of the United States, i.e. 18 percent of the American total -- that it is quite impractical to even consider doing the lot. So I will concentrate on the early years, up until the 1850s, during which all of the fundamental stove types emerged, and the Capital District's importance was at its peak. This was particularly the case with respect to patents for designs rather than functional "improvements": in the 1840s, 45 percent of all U.S. stove design patents were issued to Capital District residents; in the 1850s, when other production centers began to do more of their own work rather than commissioning it from Albany and Troy, they still contributed 38 percent of the national total. Comparable figures for improvement patents are just 12 percent in the 1830s, 17 percent in the 1840s, and 14 percent in the 1850s, though in terms of those that were fundamental to the way stoves were built and worked Capital District patents were disproportionately important. So, to a large extent, the history of Albany and Troy stoves in these decades is the history of American stoves, full stop.

Note: From the early 1850s on there is another category of source material that will provide anybody interested with a good way of seeing the industry's huge product range -- the stove catalog -- to which I have provided an online guide in this blog post. Here, for example, is what may have been the very first, and certainly the oldest to survive in an online version: Albany designer Samuel Vose's Illustrated Book of Stoves, 1853 -- a model others soon followed. See the 1854 G.W. Eddy and Rathbone & Kennedy, 1856 Newberry & Filley, 1857 McArthur & Co., and 1861 Potter & Co. catalogs.

Before the Great Fire: 1810-1836

In December 1836 the US Patent Office in Washington, DC, burnt down, and most of the records of the first 46 years of the American patent system were destroyed. Holders of pre-Fire patents were given the opportunity to restore their old ones, a process that carried on for years. A record of all pre-Fire patents was also reconstructed, and patents were given a serial number with the suffix "X". But most of these records consisted of nothing but the barest details -- a short title, a date, and the names of patentees and of the towns, cities, or counties from which they had lodged their applications. They are still worth reporting here, because they give an indication of the slow increase in the frequency with which Capital District residents began to take an interest in stove innovation.

Stoves were quite new and uncommon in the upper Hudson valley in the 1810s, and still mostly imported from southern New Jersey / south-east Pennsylvania iron furnaces throughout the 1820s and into the early 1830s. But they soon became accepted, and the Capital District began to acquire a growing number of merchants, artisans and others interested in using, making, and trading in them, from whose ranks most patentees were recruited. (For the growth of the Albany and Troy stove trade from the late 1820s -- including a running total of the number of firms active in any particular year -- see this spreadsheet; for this phase in the history of the industry, see Chapter 2, esp. pp. 2-3, 16-19, 56, and Chapter 4, esp. p. 19, pp. 23-28, from my abandoned book about the coming of the stove and the rise of the industry dedicated to making it).

In the list that follows, key details for patents that were restored, in whole or in part, after the Fire (sometimes just their drawings seem to exist in the Patent Office online copy; or drawings are associated with the wrong description, but this is usually obvious), are highlighted in bold, whereas those destroyed and not restored are in plain text. In some cases two names are given, with an oblique / between them: these are patents where the drawings and the text have different titles, probably because the illustrations were re-drawn for the Patent Office decades later. In a few instances I will include illustrations, but in most entries there should be enough information in my descriptive text for this not to be necessary, especially as the online version of the original document is only a click away, for anybody who wants to look for him or herself. I have recorded patent numbers in the form e.g. X4368 because this is the way they need to be entered into the USPTO Database's search engine. The proper format would be 4368X.

It will become clear that, had it not been for the work of the Reverend Dr Eliphalet Nott, principal of Union College, Schenectady, this list would have been much shorter and far less significant. I have included his non-stove patents too simply in the interests of completeness, and also to show the breadth of his work and the way his focus shifted from the anthracite stove to a related question, adapting the steam-powered riverboats so important to commerce on the Hudson to run on anthracite too.

|

| Eliphalet Nott, from the Union College collection |

Nott's large number of stove patents did not result so much from the value of his work -- only a few of the products that came from his inventions were commercially successful, at least for a period -- as from the way he approached patenting. In the beginning he seemed to be reporting on his experiments in the "Evolution and Management of Heat" as if in a scientific journal, rather than laying claim to intellectual property in particular devices for burning anthracite efficiently. But he was, in fact, very interested in making and selling them, and raising money for his family and college in the process. To this end he prosecuted imitators who infringed on his patents, and in 1833 took out numerous new ones to cover the improvement of individual key features of his stoves that resulted from experience and continuous experiment, the better to protect his market position. Then, in the early/mid-1830s, he also began to attempt to extend his product range beyond the market segment he had created and still dominated (large, ornate, and expensive heaters for the parlors and halls of the wealthy, and for commercial spaces and public institutions) to include cook stoves for which the demand was much greater. In this effort he was less successful, but his idiosyncratic attempts also left numerous traces in the patent record, far more than any other Capital District stove maker of the time. Nott gave his neighbors and rivals a model to emulate.

Cooper, C.D.

Albany

Fire-place

June 27, 1810

Spencer, J.

Albany

Kitchen Stove

February 8, 1813

X3064

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Fire-place

February 3, 1819

X4189*

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Evolution & Management of Heat

|

| The Nott stove in its evolved form -- ash drawer in the bottom of the firebox, fuel magazine above it (with decorative cover), "stove-pipe" i.e. heat exchanger above that. |

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Rotary Grate & Floor

March 23, 1826

DRAWING ONLY. A key feature of Nott's stove was a rotating "dumping" grate made of circular cast-iron segments on a spindle, to enable the easy cleaning of clinker and ash from an anthracite fire without having to let it go out first, so that it could be kept burning for days at a time.

X4477

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Evolution, &c., of Heat

21 June 1826

X4622

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Evolution & Management of Heat

29 Dec. 1826

X4772*

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Steam-Boiler Water Tube / Evolution & Management of Heat

30 May 1827

DRAWING ONLY -- showing how early Nott's interest in what eventually became his "Novelty" steamboat developed. The fullest account of the results of Nott's costly, in the short term unproductive, and even disastrous experiments and speculations is contained in his partner and agent Neziah Bliss's affidavit to the New York State Senate investigation of Nott's and Union College's entangled finances in 1853; their eventual success is discussed by Frederick M. Binder, "Pennsylvania Coal and the Beginnings of American Steam Navigation," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83:4 (Oct. 1959), pp. 420-445 at pp. 429-31.

X5048

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Grate / Evolution & Management of Heat

26 Mar. 1828

DRAWING ONLY -- contains his circular grate, as above.

Sanborn, P.E.

Troy

Applying Heat by means of Iron Castings & Grates for Cooking

June 11, 1829

X???? (no number assigned)

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Evolution & Management of Heat

17 Sept. 1832

X7258

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Magazine Stove / Anthracite Coal Stove adapted to Open Fire-Places

October 25, 1832

DRAWING ONLY -- includes rotary grate.

X7635

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Damper

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Gates, G.F. & Boyd, D.

This was the first in a suite of patents Nott filed on the same day which aimed to establish more securely his intellectual property in all the key features of his anthracite stoves. They had been copied (pirated) by several competitors of whom the most persistent had been James Wilson, New York's largest stove merchant-manufacturer, notwithstanding his legal efforts to stop them. These 1833 patents were the ones he chose to restore after the Great Fire of 1836, not their predecessors of 1826 on which his business had been built until then.

The DRAWING is of chimney dampers; the DESCRIPTION is of improvements in the anthracite stove including "closing the ash pit, illuminating the front, & transferring the door to the top." This sort of confusion between drawings and text is common in the Nott patents. Patent Office clerks reconstructing them when they were restored after the fire seem to have had a hard time deciding which should go with which.

X7636

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Grate / Anthracite-Coal Stove

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Gates, G.F. & Boyd, D.

There is an excellent DRAWING of the improved grate, with its separate (moving) grate-bars. But the accompanying DESCRIPTION is of using cast-iron "sash" instead of the previous copper or sheet iron, for the mica fronts of stoves, to prevent "warping & sullying." This is Nott's CASE No. 2 -- his improvement depends on "cast iron, a cheaper & less elastic material," and the text includes details on construction: his window bars were 3/16" deep, 1/2" thick, and could have "any convenient external form, though an architectural one is preferred." In practice Nott's stoves were mostly ecclesiastical Gothic, but with some Classical features.

X7637

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Refining Iron & Steel / Anthracite-Coal Stove

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Gates, G.F. & Boyd, D.

The DRAWING is of a stove (with circular grate, as in patent 7636X), fire-brick lined, and its damper arrangements. The DESCRIPTION is of an "improvement in the construction of the vertical grate and in the manner of combining therewith the sash for mica and the inlet for fuel in an anthracite coal stove." This is Nott's CASE No. 3 -- "Whereas inconvenience has arisen from the falling out of ashes on opening the illuminating sash in front when hung as usual at the side or top, and also from the warping of a fixed front grate especially when of considerable horizontal extent."

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Heating Stove / Anthracite-Coal Stove

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Boyd, D. & Gates, G.F.

CASE No. 4: improvement "in the lining between which and the front plate, the flue for the ascent of air from and descent of ashes to the ashpit is formed." The answer to the problem of the warping of the lower [cast iron] lining section of stove is to substitute a "separate moveable plate" which facilitates its removal and replacement.

X7639

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Stove Pipe / Anthracite-Coal Stove

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Boyd, D. & Gates, G.F.

There is a superb DRAWING of the tall and impressively decorated cast-iron flue/heat exchanger on top of a Nott stove, but the DESCRIPTION is completely different. CASE No. 5 was an "improvement in preventing the escape of heat from the top of a pile of ignited fuel by placing over the same a moveable plate."

X7640

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Damper / Anthracite-Coal Stove

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Gates, G.F. & Boyd, D.

CASE No. 6 was "an improvement made in the construction of the tops of coal stoves by a combination of sections, either cast separately or formed by dividing the same after having been cast entire. Whereas inconvenience has arisen from the cracking of the tops of coal stoves, which tops have hitherto been cast entire, therefore an improvement has been introduced & the same having been tested by repeated experiments is deemed worthy of being carried into general use..."

X7641

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Refining Iron & Steel / Anthracite-Coal Stove

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Gates, G.F. & Boyd, D.

CASE No. 7 -- actually for chimney dampers and stovepipes -- had also been "perfected and tested by repeated experiment." Nott represented himself as a scientist rather than an entrepreneur. He was certainly an experimentalist at his "stove laboratory" in Union College.

X7642

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Gas Furnace / Anthracite-Coal Stove

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Gates, G.F. & Boyd, D.

CASE No. 8 -- "an improvement made in the construction and adjustment of the brick forming the flue employed in confining combustion to the base of the fuel contained in Anthracite coal stoves." The problem was that the front brick usually burnt away first, and "in repairing the same inconvenience has arisen." Nott's answer was to redesign the brick to allow the replacement of high-wear bricks without disturbing the rest.

X7643

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Magazine Stove / Anthracite-Coal Stove Pipe

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Boyd, S.H. or J.K. & Boyd, D.

The DRAWING shows the brick-lined iron case and his rotary grate. The description is of Nott's CASE No. 9 -- "improvements made in the material, form and construction of stove pipe to be employed, where anthracite coal is the fuel in use. Whereas great inconvenience has arisen in the use of anthracite coal, from the escape of gas, where the heat has been imparted, from, and the smoke piped off in a sheet iron flue reverberated in the usual manner by elbows, as well as from the destruction of the flue itself." Nott's answer was to use hollow cast-iron pipes for the section of flue designed to heat the air of the room, giving it a large external surface for this purpose. Sections were jointed, then screwed and bolted together.

X7644

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Gas Furnace / Construction of Top for Anthracite-Coal Stoves

June 29, 1833

DRAWING ONLY

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Grate / Flue for Anthracite-Coal Stoves

June 29, 1833

Witnesses: Boyd, J.K. & Boyd, D.

Another DRAWING of his grate front, accompanied by a very prolix text. Nott's explanations for what he was trying to achieve, and why, were sometimes quite unclear, particularly in this case.

[Note that, from here on, most of the patents, including Nott's, are for cooking stoves -- the emerging Capital District industry's most important products.]

Shaw, W.

Albany

Anthracite-coal or Wood Cooking Stove

December 31, 1833

X7948

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Cooking Stove / Cooking Stove & Preventing the Waste of Heat of

January 9, 1834

Witnesses: Martin, D. & Holland, Alexander

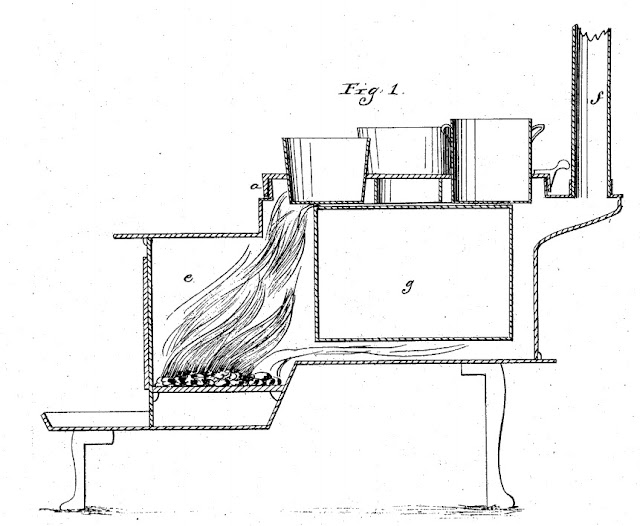

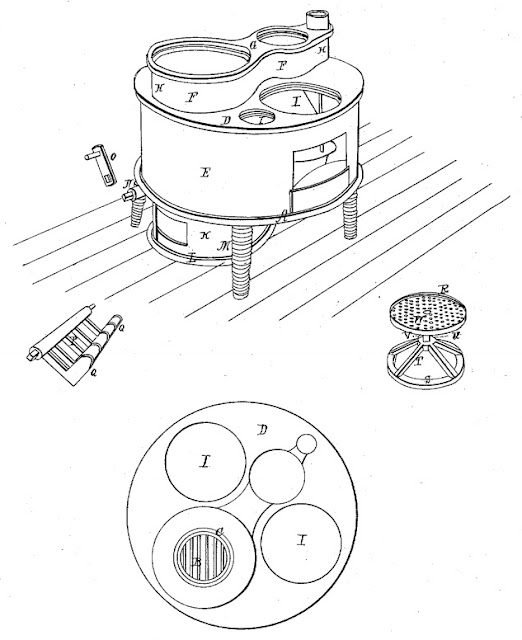

An elaborate DRAWING of a complicated circular stove. "Whereas in cook stoves having ovens under or around which the flame passes, much heat escapes to the room without producing any useful effect," Nott's design would minimize such waste by using tin or sheet-iron casing, brick and sand insulation, and ovens, boilers etc. arranged above one another. Immensely complex. See "Rotary and Circular Stoves" blogpost for more detail, and context.

By Howard Nott & Co.--A new cooking stove, by Dr. Nott, for burning Anthracite coal. The capacity of this stove was fully tested on the spot: roasting, boiling, frying, &c. &c. going on at the same time, and all done at a turn. The stove is so contrived that all these operations are kept distinct from each other -- the effluvia from each article being conducted off by separate pipes into the common smoke flue, and upon this trial nothing escaped in the least degree perceptible. There was also a parlor grate, for coal, made for a gentleman in this city, in the new style of ornament called Grecian, richly and accurately cast, and a stove of a peculiar and large capacity, intended for the Commercial Banking room, all of them in the usual workmanlike style of this firm. ["Fair of the New-York County Agricultural Society (Harlaem, 23-24 October)," New York Farmer, and American Gardener's Magazine (Nov. 1834): 325-8 at 327]

Another friendly (from the Schenectady Whig) and appreciative report demonstrates that Nott's ideas in stove design produced devices with some real apparent advantages:

We have seen a baking and cooking apparatus, the invention of Dr. Nott, which bids fair to supersede the common stove for culinary purposes, as well as the tin baker now in use for baking in front of fires, by means of reflected heat. Dr. Nott's apparatus is also constructed for baking by the reflection of heat; but its superiority over the tin baker now used, consists in its cooking and baking more quickly and perfectly -- in excluding the external air -- in taking but a very trifling amount of fuel, (three quarts of charcoal being sufficient to bake half a dozen loaves of bread,) -- and in its adaption for use in any place, -- being as well calculated for cooking out of doors, in the open air, as in the kitchen. And its superiority for the purpose of baking and cooking, over the common stove, consists in its taking not a quarter of the fuel which that requires -- in giving out but little or no heat, externally -- and in being easily moved from place to place, and put out of the way, when not required for use. ["New Bake Stove," The Genesee Farmer 4:31 (2 Aug. 1834): 247].

Treadwell, John G.

Albany

Cooking Stove

January 23, 1834

X8572

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Cook Stove / Correcting Bad Smells in Cooking Stoves

January 7, 1835

Witnesses: Jones, S/J.W. & Howard, James D.

The DRAWING shows a recognizable or conventional 4-hole stove, on standard cabriolet legs, resting realistically on an iron sheet (to prevent fires) on a plank floor, i.e. nothing like 7948X's monstrosity. The full title includes "and improving the quality and flavor of articles cooked therein." The PROBLEMS Nott was addressing were common objections to iron stoves: "the heat is variable, the smell offensive, and the quality and flavor of the articles cooked, injured." His SOLUTION: brick or stone lining between firebox and oven, tin or brass jacketing on the outside, and a steam escape vent to the flue.

Iggett, John

Albany

Portable Cooking Stove

January 16, 1835

Witnesses: Dox [?], Gerrit S. & Ward, R.E.

Iggett's stove was a sheet-iron cabinet with a small firebox underneath. He described himself as a "Tin & Sheet iron worker." It is not clear that he had actually manufactured prototypes, but he described three variant models.

X8602

Parker, Sylvester

Troy

Three-Boiler Flat Cook Stove

January 16, 1835

Witnesses: Staples, Y.B. & Shorsman, Elias A.

|

| The illustration is just a standard woodcut of an older stove type (the James stove) designed to draw the reader's attention to a stove advertisement, not an illustration of the Parker stove. |

Rathbone, Joel

Albany

Flat Cook Stove

March 6, 1835

Witnesses: Cooper, Chas. & Sparhawk, N.

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Plain-Plate or Box Cook Stove

April 22, 1835

Witnesses: Jones, S.W. & Jones, M.B.

In some respects this was like a conventional wood-fired cook stove of the time, e.g. the feet, the provision for 2 or 3 boilers on the top, and the chimney damper to control it. But in other respects it's idiosyncratic, typical of much of Nott's other work but also emphasizing his distance from the artisan-merchant community making and selling the stoves customers wanted -- e.g. the brick firebox bottom, the reflector oven on the hearth, and the smoke flue at the front rather than back of the stove. Nott thought of some of these features as answers to the problems of conventional stoves -- "the waste of fuel & the unequal distribution of heat in the oven." Nott dealt with them by getting rid of the internal oven altogether, replacing it with tin reflector ovens on the hearth and sides.

X8791*

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Steamboat Furnaces, Boilers, & Chimneys

22 Apr. 1835

X8792

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Kitchen Range for Using Anthracite Coal

April 22, 1835

Witnesses: Jones, S.W. & Jones, M.B.

Another curiosity, and a variation on 8790X. This was a 4-hole anthracite range, either 2 x 2 in a square or 4 x 1 lengthwise. It included a fuel feeder and brass or tin reflector ovens. Nott's stoves were big, expensive, and idiosyncratic, but cook stoves had not yet become fairly standardized, so it was reasonable for him to suppose that there might be room in the market for them.

X8866

Southwick, Thomas M.

Troy

Heating Stove / Wrought-Iron Stove for Burning Anthracite Coal

June 6, 1835

Witnesses: Cook, Clement J. & Elliot, J. Alfred

"Southwick's Pyramidal Stove" -- like Nott's, an anthracite-fueled space heater, but probably cheaper and in some respects more practical, e.g. the sectional construction and pull-out ash-drawer.

X9179

Nott, Eliphalet

Schenectady

Stove to burn Anthracite Coal

October 17, 1835

An amended version of his 25 Oct. 1832 patent, 7258X -- surrendered and reissued.

X9341

Ripley, Ezra

Albany

Stove-Pipe

January 23, 1836

X9350

Williams, Daniel

Schaghticoke

Cooking Stove

February 3, 1836

Witnesses: Wright, Abm. Jr. & Whiting, Daniel

A kind of step stove, with two boilers over the fire, and two over the oven. Its key feature was a complicated sliding fire-box. How practical was this feature? It certainly did not become standard, so in a sense this patent was just another dead-end. But Williams was addressing the common problems driving other stove improvers too: preventing over-heating of the oven, regulating the heat, dividing it between the oven and the boilers, "carrying off the steam." One curious feature: Williams reissued this patent in 1840 (RX28) from Troy, where he had moved (witnesses Job S. Olin and A.W. Blair), and again in 1842 (RX69, not found in USPTO). You would not expect him to have bothered to do this if it was of no value, either as a patent from which to make a salable stove, or as useful patent to block another inventor's patent. A useful consequence of the reissue is that his patent was printed, so RX28 is much easier to read, not that this makes the purpose and workability of his patent any simpler to understand.

X9451

French, Maynard

Albany

Rotary Stove-Cap

March 2, 1836

Witnesses: Dougherty, W.W. & Cushing Schuyler, Wm

French was an Albany stove maker. This was basically another step stove, coal fired, with flues over, under, and behind the oven, but with a circular 4-boiler top. It was an obvious attempt to cut into the booming rotary stove market with something presented as an improvement on both of the warring Stanley and Town patents. The language of the patent is vague -- this top "may be plain or constructed with cogs for the purpose of being moved by a pinion," and moved by "a knob, leaver (sic) or rack & pinion," with a "plane (sic) bearing or upon rollers." Thomas Jones, patent expert and editor of the Journal of the Franklin Institute, did not think much of it: "We see no essential difference between these caps and those used by Stanley nor any superior advantage to be derived from them." -- "Mechanics' Register. American Patents. List of American Patents Which Issued in March, 1836. With Remarks and Exemplifications by the Editor," JFI 18:5 (Nov. 1836): p. 317.

Schenectady

Steam-Boiler Furnace / Steam Generator

19 Mar. 1836

Witnesses: Jones, S.W. & Duane, Cornelius

Another steamboat boiler patent.

Robertson, R.

Albany

Stove, Conical

June 16, 1836

X9805

Douglas, Beriah

Albany

Cooking Stove

June 30, 1836

Witnesses: Elliott, William P. & Salomon, S.G.F.

The DRAWING for this patent and 9806X's are paired with the other's DESCRIPTION (they shared a common and distinctive firebox). I'm swapping them around here. The patent text for Douglas's circular cooking stove provides full details of construction, dimensions etc. "The fuel designed to be used principally in this stove is the Anthracite coal, but wood may also be used by altering the shape of the fire box." Douglas's was evidently a very merchantable product -- see Clute & Billings ad. in The Schenectady Cabinet: or, Freedom's Sentinel 26 Mar. 1844, p. 1: even eight years later it was still "The Best Stove Out. Douglas' Patent Cooking Stove."

X9806

Douglas, Beriah

Albany

Heating Stove / "Improvement in the Cooking Stove"

June 30, 1836

Witnesses: Elliott, William P. & Salomon, S.G.F.

An ornamental parlor stove, with a plate surrounding the firebox (which seems to have been shared with the cooking stove) "perforated all round in a tasteful manner ... to suit the fancy of the constructor." Its purpose was "to faciltate the diffusion of heat, soften the glaring appearance of the inner cylinder when red hot, and give to the stove symmetrical proportions and beautiful appearance."

X9842

Pratt, E.N.

Albany

Stove, Cooking

July 1, 1836

X9889

Parmalee, W.

Watervliet

Stove

July 2, 1836

DRAWING only: a standard 3-boiler step stove, but with a divided sunken hearth, allowing for an additional small boiler [or something: maybe a small fire-pot for summer use?].

And at that point the old patent series ended, and a new one, implementing the more formalized requirements of the 1836 Patent Act, began.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments will be moderated to prevent spamming, phishing, and advertising. If you wish to do any of these things, please don't waste your time and mine.