|

In 1867 Edwin Freedley wrote up the company whose plant was illustrated in the above full-page engraving in these terms: Probably the largest establishment engaged in the casting of stoves in the city is that of Sharpe & Thomson, successors to North, Chase & North, who were prominent Stove Founders in the city for twenty years. This firm have in connection with their works six acres of land, located between Second Street and Moyamensing avenue and Mifflin and McKean streets. The buildings are of brick, and include two of immense size. The Moulding Room, which, it is supposed, is the largest in the United States, has a front of one hundred and one feet on Second street, and a depth of three hundred and five feet on Mifflin street, containing over thirty thousand square feet. In this are two cupola furnaces, capable of melting eighty tons of iron per day. The Finishing Department and Wareroom occupy another extensive building two hundred and sixty-eight feet long, and sixty-eight feet wide. Besides these immense structures, there is a building seventy-one by eighteen feet, in which the offices connected with the foundry are located, a Pattern Store Room, one hundred by eighteen feet, and numerous auxiliary buildings necessary to the successful prosecution of the business on an extensive scale. There is an Artesian well on the premises, which supplies water for the engine and boilers. Almost three hundred men are employed, and twenty-five hundred tons of No. 1 American iron are converted into Stoves annually. Besides Stoves, Messrs. Sharpe & Thomson manufacture Tinned and Enamelled Hollow-ware of a fine quality, as has elsewhere been stated, and, in addition to their manufactories, the firm have a large five story store, at 209 North Second street, which is one hundred and fifty feet in length, and filled with samples of their various productions, presenting an assortment of unsurpassed attractions. The salesrooms are in charge of Mr. Charles Sharpe, while the Manufacturing Department is under the supervision of Mr. Edgar L. Thomson, an experienced founder. What was the firm's history? Simeon Harrison and Gibson North set up as stovemakers with premises at 390 High (Market) Street in 1845, and as North, Harrison & Co. remained there until 1851. They are reported to have owned a foundry in Wilmington, Delaware, which was said to be the source of their castings, but I can find no trace of it in city directories and local histories, so I assume that they may simply have had a stake in or contracts with one of the smaller local foundries, most likely James Rice's. (The other three, Betts & Seal, Bush & Lobdell, later the Lobdell Car Wheel Co., and Evan Stotsenburg's have left records and/or descriptions of their business which are silent about any such contract, and their reported products did not include stoves. Betts & Seal and Stotsenburg were jobbing or semi-specialized machinery foundries; Bush & Lobdell were already specialist chilled iron car wheel manufacturers). In 1848 they gained a third partner, Pliny Earle Chase, b. 1820, a Harvard-trained mathematician, scientist, and private-school teacher, and friend of Edward Everett Hale, William Ellery Channing, and other Yankee luminaries, who had been advised by his doctors to find a new field of employment better for his diseased lungs, and allowing "more outdoor air and exercise." Curiously, he chose stove-making. [Garrett, "Memoir of Pliny Earle Chase," (1887), p. 289.] Friends wondered at this, but he explained that he had to make a living. [Green, "Pliny Earle Chase," (1887), p. 318.] Gibson's brother Asa joined them in the partnership, briefly renamed Norths, Harrison and Chase, in 1851, having already been involved in the business: he and Chase were both witnesses to North's first patent, No. 6943, "Making Tin Boilers ... with Cast-Iron Bottoms," in 1849, a way of constructing a cooking utensil with a cheap, durable but also rust-proofed (via a tin, zinc, or enamel coating) bottom and sheet-metal sides and top soldered to it. The firm also received a substantial injection of capital: John Edgar Thomson, b. 1808, chief engineer and, from 1852, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company became their special partner in 1850 (this meant he could invest and share any profits, but his liability was limited to the amount he had invested, provided he did not participate in management). This may have enabled them to bring castings production back to Philadelphia rather than continuing to rely on a less convenient, because harder to supervise, source of supply in Wilmington thirty miles away. (Chase and Thomson were both birthright Quakers; it would not be surprising if this partnership was rooted in that local religious community, but I cannot find out anything more about Harrison and the Norths, so this must remain speculative unless there is something in Chase's biographical notes, available, though not easily to me, on microfilm -- p. 5 of catalogue, Box 1, Folder 8.)

In 1852 Harrison died and the partnership changed its name again to North, Chase, and North. The North brothers also altered their occupational and business descriptions: they were now iron founders, with a small foundry at 145 North Second Street, almost opposite James Yocom's on Drinker's Alley. That was where they were when Gibson took out his second patent, again suggesting that his principal expertise was still in metal plating. This one, No. 9948, was for an enamel lining for cooking stove and range oven doors, intended and claimed to "prevent the escape of heat" and, by "retaining and equalizing the heat of the oven," render it "a more uniform, economical, and efficient baker." Once again Chase witnessed the patent, together with Anson Atwood, b. 1810, an experienced stove inventor from Troy, New York, where he had owned and run the Empire Foundry between 1841 and 1846, and taken out seven patents between 1838 and 1850. It is possible that Atwood may have been lending his expertise to the partners as they learnt the ropes of the stove manufacturing business.

One reason that North did not need to design his own stoves like Cresson and Warnick, who had preceded him in entering the foundry trade, is that by the early 1850s there was a small group of specialized pattern makers emerging in the city who would do the job for foundrymen. The partnership of Garretson Smith and Henry Brown became the most productive and influential among this group -- and North, Harrison, and Chase gave them their first Design Patent contract, in 1852.

Note the fine small drawings of the profiles of particular parts of the pattern. Stove design patents do not usually show a head-on view of cooking stoves, so this one is particularly welcome as well as handsome. North, Harrison & Chase's name would have been on the panel beneath the ash box and above the two removable hatches for cleaning out the flues beneath the oven. The flues can be seen projecting below the bottom of the stove. Checking through Smith & Brown's 102 stove patents (38 percent of the city total of 271 between 1850 and 1873) to see which were assigned to (bought and/or commissioned by) North, Harrison & Chase and North, Chase & North will enable me to get a better sense of what they made and sold. [t.b.c.] Meanwhile, as a sort of placeholder, here is a nice box stove which has survived the last 150 years and is now in some lucky person's private collection:

Small 1850s Box Stove sold by Pook & Pook, Inc., auctioneers, 2012. One cooking hole in the top plate and a covered ash drawer in the front hearth.

* * *

It was 1854 before Chase finally changed his recorded occupation, to stove dealer, at the old Market Street address, which highlights a problem with using city directories as a source: the information they contained was only as complete, reliable, and up-to-date as their informants supplied; presumably he was running the store while the Norths managed the foundry. But by the end of 1856 he, too, called himself an iron founder, and the old Market Street premises had been given up. The Second Street address was now the temporary office and warehouse, and a new foundry had been set up at Second and Mifflin in South Philadelphia -- like Savery's, Cresson's, Warnick & Leibrandt's, and Abbott & Lawrence's, on the fringes of the city center if not even further afield, and with room to spread out. They had a whole block bounded by Mifflin to the north, Moyamensing Avenue to the west, McKean to the south, and Second (now renamed Third) to the east. The following year they moved their downtown address to more suitable business premises a little further up the street, i.e. by the end of 1857 the company had taken possession of both of the locations where it remained even under new ownership, as shown in the 1867 illustration at the head of this essay. The foundry is the building on the right, the "mounting room" (still marked as such on Bromley's 1895 city atlas, the first to cover this newer part of the city in detail) the long, low building to the rear. All that seems to have happened in the forty years between building the new foundry and Bromley's survey is that a few smaller structures began to fill in the large open square between the original two wings.

The foundry in 1891, from a slightly different angle, showing extensions and infilling. See also this zoomable map of about the same date.

In 1858, the company's first full year in its new foundry, North took out his third and last patent, No. 22147 -- an improvement to the firebox of the "Complete" style of cooking stove, a Philadelphia favorite, or of any other kind for that matter, designed to make it burn more efficiently and economically by pre-heating the air, and also to prevent the plate between the firebox and the oven from burning out. North was still not patenting whole stoves, but he had evidently acquired the experience and skill required to make a valuable improvement to them.

Asa North withdrew from the business in 1858, and Gibson in 1863, so Pliny Earle Chase, despite his reluctance, became its head -- by that time, thanks to the health-giving properties of his time in the company offices, sales room, and foundry, his lungs had recovered -- with new partners including J. Edgar Thomson's nephew Edgar L. who joined in 1859 or 1860, and Charles Sharpe, formerly a boot and shoe merchant, who replaced Gibson in 1863. President Thomson married late, in 1854, and had no children, but his nephew was evidently close to him, and a member of his household; had he served a "premium apprenticeship" with North and Chase before coming into the partnership his uncle bought for him? He already described his business as "foundry" and "stoves" in 1860 and 1861, and one of Chase's obituarists identified one of his younger partners and successors as a former employee. But, according to Thomson's biographer, the $62,000 cost of young Edgar's partnership was only paid in 1863.

Chase also resumed his scholarly activities part-time in 1858, alongside his proprietary and executive responsibilities, enough to win himself election to the American Antiquarian Society in 1863, and the Magellanic Gold Medal of the American Philosophical Society in 1864 for his paper on "The Numerical Relations of Gravity and Magnetism." At the end of 1861 he once again described himself as a "school teacher," having bought a private school, but by the following year he was back to being officially, though evidently not wholeheartedly, an iron founder again. This was during the turbulence of the Civil War, when the company turned out shot and shell for the Union forces, and endured severe difficulties with its restive unionized stove molders as a result.

Philadelphia Press 1 June 1861, p. 3.

The fact that the mild-mannered and scholarly Chase was also devoting an increasing amount of his time to his true vocation detracted from his attention to trade, to which he was not in any case very well suited. As his obituarist put it, "the practical business element was somewhat deficient in the head of the house, who greatly preferred intellectual pursuits, and, after suffering heavy losses" -- hard for a Philadelphia foundryman to manage during the great prosperity of the war period, but evidently not impossible for a genius like Chase -- "he finally, in 1866, after having wasted eighteen precious years in uncongenial occupations, sold out his interest in the foundry business," leaving Sharpe & Thomson running the show much more profitably than he ever had. Free at last of his unwanted and distracting duties, Chase was able to devote the last twenty years of his life to a much more rewarding and productive career as a faculty member at Haverford, where his younger brother Thomas taught and then served as President, and also for short periods at the University of Pennsylvania and Bryn Mawr College. He became internationally recognized for his research and speculations in an astonishing variety of fields, but principally meteorology and physics. And, freed at last of Chase's leadership, Sharpe and Thomson were able to take the company to the position as largest of Philadelphia's stove and hollow ware foundries where Freedley found and reported it when he updated his invaluable guide to Philadelphia and Its Manufactures to take account of the changes wrought in the decade since his first edition.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

Total Pageviews

Sunday, January 21, 2018

North, Harrison & Chase, later Sharpe & Thomson -- Philadelphia Stovemakers, 4

The Liberty Stove Works -- Abbott & Lawrence and Charles Noble: Philadelphia Stove Makers, 3

Abbott and Lawrence Liberty Stove Works. Brown Street above Fourth, c. 1852 -- zoomable image.

In 1856, when Edwin T. Freedley published his Leading Pursuits and Leading Men: A Treatise on the Principal Trades and Manufactures of the United States (Philadelphia: Edward Young, 1856), he devoted most of his report on the city's emerging stove manufacturing industry to a single relatively new firm, Abbott & Lawrence's Liberty Stove Works. This may be because they had paid or otherwise encouraged him: his report was a sort of advertorial, but nonetheless worth quoting at length.

Messrs ABBOTT & LAWRENCE, Brown Street above Fourth, have one of the largest stove foundries in Philadelphia; and as they are men who deservedly occupy a leading position in this pursuit, a notice of them must suffice for all. The spacious buildings occupied by this firm were erected in 1851, and consist of a four story brick warehouse and mounting rooms, on a lot having a front of 360 feet on Brown Street. The moulding room is on the rear of the lot, and is 360 feet long and 60 feet wide, -- the largest moulding room, we believe, in the United States. The engine room, pattern rooms, &c. are in a building extending from the warehouse back 60 feet.

Although Messrs. Abbott & Lawrence have been in business but little more than four years, yet such has been the popularity of their manufactures, that they now make about 2500 tons of stoves per annum [c. 20 percent of the city total], and the demand is constantly increasing. This unusual success is, no doubt, the result of the minute knowledge of the business possessed by the members of this firm, and the attention which they give to the excellence of their castings. Both the gentlemen composing this firm are men practically versed in all the details of the stove manufacture, having been for many years connected with another well-known establishment [not named, but Warnick & Leibrandt]; and in fineness of their castings, the stoves made by this firm are not excelled by any other. In fact, their stoves may easily be mistaken for the celebrated castings of Barstow [A.C. Barstow of Providence, RI] who bestows so much labor and expense upon them; and such is their reputation wherever introduced that other manufacturers have, in many cases, been supplied with them.

Messrs. Abbott & Lawrence have every variety and style of stoves embracing about 150 different patterns. [pp. 278-9]This was the company that had chosen to mark its entry onto the field of competition, and the opening of its brand-new, purpose-built foundry, by commissioning W.H. Rease to make a fine engraving of it.

Unlike Warnick & Leibrandt's new foundries, but like Cresson's, James G. Abbott and Archilus Lawrence's was built on a city block which would become much more crowded over time. But when it was constructed there was still room around it for open-air storage of raw materials. The image shows part of the large foundry building with a smoking cupola furnace, and laborers wheeling pig iron, scrap, anthracite, and limestone up to the charging platform. The other large building was the usual combination of office, work rooms for stove finishing and assembling, and a lot of storage. The stove industry's demand was highly seasonal -- late summer and early winter were peak periods -- so companies needed to be able to pile up the year's production to be able to satisfy it. The wing projecting back towards the foundry contained the boiler and steam engine to drive the air compressors for the cupolas and the small amount of other powered machinery (tumbling barrels to clean castings, a machine shop) on the floors above. The only feature worth zooming in on is the group of stoves lined up on the pavement in front of the main building -- a step stove, an open Franklin with a decorative urn on top, and another couple of heating stoves, i.e. typical products of the kind one can see in other Rease engravings and in the 1861 Leibrandt & McDowell catalogue.

* * *

Abbott & Lawrence's partnership began in 1851, according to a late nineteenth century history of the firm, i.e. the same year in which they built their works. James G. Abbott showed up in the 1850 directory as an iron founder, and before that as a merchant; Archilus Lawrence (b. 1819) made his first appearance in 1851 with an iron foundry at Washington Avenue above Noble, i.e. Warnick & Leibrandt's Philadelphia Stove Works, and a house at Fourth above Willow. In 1852 he was still living at the same address, but his foundry was now at Fourth and Brown, as shown in the engraving.

This is interesting, because it raises the question of what Lawrence was doing at the Stove Works, and where Abbott was working as an iron founder, beforehand (that description, like many occupational labels used in the directories, is ambivalent: it refers to both a business and a role, i.e. an iron founder could be either or both of a senior skilled supervisory or managerial employee in a foundry, or its proprietor).

The answer comes from Joseph A. Barford's "Reminiscences of the Early Days of Stove Plate Molding and the Union," Iron Molders' Journal 38:3 (March 1902): 179-82. "Archie" Lawrence had been the superintendent of both the Germantown Road and the Washington Avenue foundries since at least 1847. And Abbott was one of the witnesses on Warnick & Leibrandt's Design Patents D120 in 1847, D179 and D199 in 1848, and D312 in 1850; in 1850 all four men including Lawrence jointly patented a portable furnace, D276.

What all this says is that the new firm was an offshoot of the old, which helps explain why even its architecture and layout were so similar, as were its business practices and its early products (cook stove designs D431 and 432, and the furnace D454, all in 1852), illustrated below. They even commissioned Rease to do his very similar engravings of their new works. One question to which there is probably no available answer is whether the active partners in the old firm also put up some of the capital for the new one -- common practice among proprietary Philadelphia firms at the time.

|

| This was the bog-standard mid-century stove type, the large-oven square cook. |

|

| The "Complete Cook" seems to have been a distinctive Philadelphia variant on the step stove, shorter and with a much more pronounced step. Leibrandt & McDowell were still selling them ten years later, and had been since the late 1840s. |

The way they did this was like their parent company -- by buying new designs from the city's (and other cities') pattern makers. A & L's advertisement in Freedley's book, or at least its placement, emphasizes this:

Just as they did in Freedley's advertorial text, A & L shared their advertising page with their principal designers, Garretson Smith and Henry Brown, for whom they were the main customers through the rest of the decade.

[more -- include other 1850s designs]

By the time they published their first post-Civil War catalogue in 1867, their claims on their own behalf were quite explicit, though -- as usual with the stove trade -- not necessarily 100 percent true: All of our stoves are patented, and must not be used to be cast from. Any person infringing will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.They were selling "the largest and best assortment of COOKING, PARLOR, and HEATING STOVES ever offered."

While great attention has been paid to STYLE AND BEAUTY OF DESIGN, care has been taken to combine STRENGTH and DURABILITY, and as no pains or expense have been spared, they cannot fail to give satisfaction. [pp. 4-5]

* * *

Lawrence died in 1859 but had already left the partnership, which changed to Abbott & [Charles] Noble in 1858; Abbott retired at the end of the 1860s, and from 1870 onwards the firm was Charles Noble & Co.

|

| The 1852 "Complete Cook" is in the front row, third from left. Cook stoves at the bottom of the pile, heating stoves further up. [Link] |

* * *

For the growth and changing appearance of the Liberty Stove Works as it filled in its block, see the following pictures from the 1867 catalogue, and these Hexamer Insurance Surveys: c. 1870, 1875 (which gives 1851 as the date of the first buildings on site), and 1894.

|

Liberty Stove, c. 1891 -- the original buildings were the foundry at the rear, the left side of the quadrangle, and the left half of the street frontage.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sources:

|

William Penn Cresson, later Stuart & Peterson -- Philadelphia Stovemakers, 2

William P. Cresson's Foundry, Willow above Thirteenth Street, Philadelphia, August 1847 -- zoomable image.

William Penn Cresson (b. 1814, retired from active business 1857), a member of a distinguished local Quaker family, was a hardware merchant before he decided to invest in a new foundry to manufacture within the city the goods that he traded. This was built on about half a block in the Spring Garden manufacturing district of the city, bounded by Broad, Hamilton, Thirteenth, and Willow [later James, now Noble] Streets, with good railroad service rather than waterfront access. The online version enables one to see men charging the cupola furnaces from the outside; piles of pig iron outside the boiler and steam engine house, with its tall chimney; a molding flask leaning against the wall; a molder pounding sand just inside the door; the modern, well-lit wide-span molding floor; and the horse tram bringing in fuel from the railroad running down the street nearby. There seems to be one big difference from Warnick & Leibrandt's and Abbott & Lawrence's foundries (see below): the apparent lack of multi-storey warehouse space on site.

Thanks to an 1849 broadside, we can see, perhaps, part of the explanation: Cresson may have produced more hollow ware and fewer stoves than they did, or planned to. Or perhaps, as a merchant, he already had warehouse space elsewhere?

|

| Zoomable original at Historical Society of Pennsylvania. |

I am not entirely sure why a hollow ware foundry required less warehouse space than a stove foundry, but perhaps it had to do with a steadier, less seasonal pattern of demand, so that products could be shipped through the year? The city's other major hollow ware foundry suggests as much.

Savery & Co. Iron Hollow Ware Foundry, August 1847 -- zoomable image.

The Philadelphia branch of the Savery family businesses was established in 1838, and winning prizes for its hollow ware, by 1840. Its foundry, on South Front Street between Reed and Dickinson in what was then an urban-edge neighborhood of South Philadephia, was in business by the end of that year. It looks smaller than, but otherwise not dissimilar to, Cresson's. Ware is stacked in the front yard, and going to market (or to the waterfront) by horse and cart.

* * *

To revert to Cresson, there is little apart from that broadside to describe his business and its products, except for an impressive spate of Design Patents that he took out as he established it in the stove market [see the Warnick & Leibrandt post for their similar efforts]:

- in 1846 D48, for a Summer Furnace; D75, jointly with David Stuart and Jacob Beesley, for an elegant heating stove; D88, for a cooking stove, with the same partners plus Samuel H. Sailor; and D100, for a (probably cooking) stove plate, with Stuart and Sailor;

|

| The Summer Furnace -- for outdoor cooking, or to use instead of a regular cooking stove. There is no stove pipe because, if used indoors, it would be placed on the hearth of an existing fireplace. |

- in 1847 D108, with Stuart and Beesley, more cooking stove plates; D116, the same, for a very patriotic design emblazoned with the American eagle and the slogans "Ne Plus Ultra" and "E Pluribus Unum"; and D117, with Stuart, Beesley, and Sailor, for a coal heating stove;

- in 1848 D163, with all the same partners, for a cooking stove, and D171, with Stuart and Beesley, for another elegant heating stove;

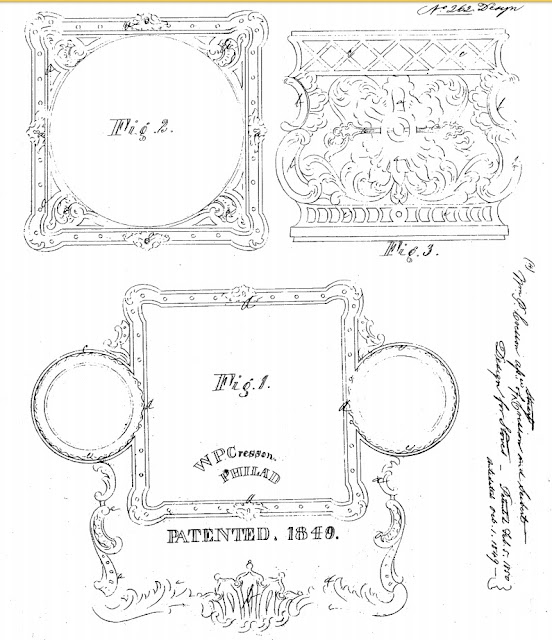

- finally in 1850 D261, for an even more attractive oval heating stove, the "Cottage Parlour Air Tight," with Stuart and a new partner, Peter Seibert, and D262, the "Radiator Screen" heating stove, with the same partners, and both "beautifully carved"; D270, the "Cast Iron Parlor Air Tight" with "very pretty" decorations, and D271, similar.

|

| D261 -- from top left, the mid-section ring, on which the oval wrought-iron body would be fixed; door and other smaller plates, including a leg; the top plate; and the bottom or hearth plate. See here for Leibrandt & McDowell's similar products. |

|

| D262. Many heating stove designs only include the more important cast plates -- in this case (clockwise from top left) top, mid-section, and hearth plate -- because the rest was fabricated by local smiths from wrought-iron plate. This seems to have been a square column for the firebox and main air chamber, flanked by two cylindrical pipes to radiate extra heat, as can be seen in some of the stoves in the Rease engravings. [See this Leibrandt & McDowell example, and compare Charles Gilbert's much more elaborate take on the same layout, above.] |

|

| D270. for an all-cast "air tight" stove, showing (clockwise from top left) a side, a leg, the top, the bottom or hearth plate, and the front (or, with a stove pipe collar in place of the air register, back) plate. |

|

| D271 -- from top left, a leg, the bottom or hearth plate, the air register plate, the feed door, and the top plate. |

|

| D261 -- from top left, the mid-section ring, on which the oval wrought-iron body would be fixed; door and other smaller plates, including a leg; the top plate; and the bottom or hearth plate. |

These patents show us more than just Cresson's and his partners' artistic ability and their, and presumably their customers', tastes. They also, like Warnick & Leibrandt's and Abbott & Lawrence's, cast light on their business connections. Who were Cresson's partners in design? Jacob Beesley was already in business as a pattern maker in 1846. The only Samuel Sailor in the city was described as a laborer, and David Stuart did not show up at all, unless perhaps as D.J., a clerk. It was 1851, by which time Sailor began a long and successful career of design patenting as sole or first-named patentee, before he first appeared unambiguously in his own name, as a carver. Beesley's independent patenting career began the following year, with the firm soon to be renamed Cresson, Stuart & Peterson among his clients. Cresson had clearly launched two of his younger associates into the artisan enterprises they would follow after he laid down his drawing pen, and the other, Stuart, he took into partnership to enable him to withdraw from active business with his "competence" achieved by 1857, allowing him to devote the rest of his life to philanthropy and community service. The other names on patents are those of their witnesses. Cresson's most frequent witness -- on four patents in 1847-1848 -- was Richard Peterson, eventually his other new partner.

There are two later accounts of Stuart & Peterson's business as it stood before and after the Civil War, in both editions (1857, published 1859, and 1867) of Edwin Freedley's invaluable Philadelphia and Its Manufactures.

* * *

Three of the Foundries in Philadelphia are occupied almost exclusively in casting Hollow-ware and Hardware Goods, which are subsequently enameled or tinned. The establishment of one of these, that of Messrs. STUART & PETERSON, is probably more extensive than any other of the kind in the Union. In this manufacture great care is necessary in the selection and commixing of the different brands of Iron, in order to obtain castings of proper tenacity ; and after such are obtained, the inside surface of the ware must be made smooth and bright to protect the enamel. In England this is effected by turning the article in an ordinary foot-lathe, the tool being guided by hand ; but the inhalation of particles of Iron proved most destructive to the lives of the operatives. The firm above alluded to, employ for this purpose self-acting tools or lathes, the invention of their master-machinist; and so admirably do they conform to the irregularities of the surface to be turned, that they seem to be endowed with almost human intelligence.

The products of this establishment embrace a great variety of

Culinary and Household articles -- Pots, Kettles, Stew-Pans, and other articles, from the smallest to the largest, as Caldrons, &c.

They deserved "very great credit for their successful efforts in competing with foreign manufactures."

Ten years later, Freedley repeated and extended his laudatory description of the company and its products:

Ten years later, Freedley repeated and extended his laudatory description of the company and its products:

The firm that have attained pre-eminent distinction in the manufacture of Tinned and Enamelled Hollow-ware is that of Stuart, Peterson & Co., on Noble street above Thirteenth. The foundry of this firm occupies an area of sixty thousand square feet, requiring to cover it an acre and a half of Slate Roofing. The moulding floor is in the form of a square, having a superficial area of twenty-two thousand five hundred square feet. Almost three hundred workmen are furnished employment constantly, and four thousand tons of American Iron are consumed annually.

This firm, by the adaptation of ingenious machinery, have so completely surpassed all foreign competitors in the production of Tinned and Enamelled Iron ware, that articles of their manufacture have a preference in all markets in the world. A detailed account of some of the processes and machines that are peculiar to this establishment will be found in Bishop's History of American Manufactures, to which the curious reader is referred. [p. 401]

[They also] produce about five hundred Stoves a week, or twenty-seven thousand in a year. They make all kinds and styles of Stoves that are in demand, and employ six persons whose business is exclusively to originate and prepare new patterns and designs of Stoves and Heating Apparatus. [p. 458].

|

| Stuart & Peterson's in 1862, five years after Cresson's withdrawal. The foundry -- the largest building in the 1846 engraving -- is the big shed with distinctive roof ventilators on the right of this view of the property. The 1846 viewpoint was not of the Willow street frontage but from the open space then behind it, now enclosed and filled in. |

* * *

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sources:

- McElroy's Philadelphia City Directory, 1840 through 1867.

- US Patent & Trademarks Office online patent records.

- Edwin T. Freedley, Philadelphia and Its Manufactures: A Handbook Exhibiting the Development, Variety, and Statistics of the Manufacturing Industry of Philadelphia in 1857 (Philadelphia: Edward Young & Co., 1859), pp. 291-2.

- Edwin T. Freedley, Philadelphia and Its Manufactures: A Handbook of the Great Manufactories and Representative Mercantile Houses of Philadelphia, in 1867 (Philadelphia: Edward Young & Co., 1867), pp. 457-9.

- John W. Jordan, Colonial Families of America (New York: Lewis Publishing Co., 1911), Vol. 2, p. 953.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)