The Great Partnership:

Ezra Ripley and Nicholas Swart Vedder, Troy, NY Stove Designers, 1836-1864

The recent appearance of another attractive "Severe Airtight" stove in a Facebook Antique Stove Collectors' group has encouraged me to draw together the work of its two designers, in what may be the first in a number of new posts cataloguing the output of some of the most influential and creative men (and they were all men) in the American stove industry in its first golden age.

|

| Top view with 6" boiler hole covered |

|

| Top with cover removed |

|

| Hearth showing ash pit and circular draft control |

|

| Front View -- dimensions 26" wide x 21" deep x 28" high |

|

| Side view [All photos used with owner's permission] |

The Severe Airtight was a parlor stove of the kind popular since the mid-1840s, carefully manufactured to minimize air leakage at its joints and enable the rate of burning to be regulated by a single draft control in the front hearth and (perhaps) a damper in the chimney. The fuel feed door was on the right hand side, and the stove was wide enough to take a c. 15" length of firewood. The design was in the popular "Gothic" style, with a plain, chaste surface decoration of pointed arches, columns, and diamond and other patterns.

The Design Patent drawing included above is a poor photographic reproduction, but the original (if it survives in the U.S. National Archives) would have been a very fine large-scale (1:2 or 1:3) drawing on durable but almost transparent paper. It shows the one crucial part of the stove that has not survived 170 years -- the decorative urn and finial that sat in the center of the boiler-hole cover on the top plate, and probably served as a room humidifier, filled with water and perhaps scented herbs -- and also includes other information helping us to put the stove design into its context:

- It notes that the design has been assigned to (purchased and/or commissioned by) a local firm of stove makers, Low & Hicks, who thereby acquired the designers' intellectual property rights for the patent's full period of seven years. This was a normal way of doing business for stove pattern makers. Unless they were also manufacturers themselves, they either worked on commission or developed designs in a speculative way and then sought makers to buy the right to use them. Assignment data is quite common in design patents and usually signifies that the pattern makers are working on commission; assignments issued after the patent had been granted would have been recorded separately, in one of the Patent Office's enormous Assignment Books which have not, unfortunately, been digitized yet. (The Low & Hicks partnership existed between c. 1847 and 1855. Peter Low had entered the stove business as a sole trader in 1830; George W. Hicks remained in it until 1858 after their partnership broke up, at first as a sole trader himself and then with Edward J., his ?son; Edward J. continued with a new partner, Gordon G. Wolfe, until 1877, i.e. this was a well established local firm. All data from this spreadsheet.)

- The other names on the patent are those of its witnesses. Sometimes there are separate witnesses for the drawings and the text, but not in this case. Assignee and witness names are data worth collecting for understanding the networks of local business relationships in which mid-century entrepreneurs were embedded. It would not be difficult to cross-refer names with local directories, newspapers, and censuses, but the exercise would only be worthwhile if done on a large scale. The witnesses in this case -- E.L. Brundage and A. Snyder -- included the man who probably made the drawing and filed the patent. Brundage was a draughtsman and patent agent, providing valuable specialized services to the local stove-design community.

Ezra Ripley (b. 1795/6 in Vermont) was the more established member of this partnership. He was an old hand at the business of invention, having patented a mortising machine in New York in 1825 (No. 4295X) and a wash stand in Schenectady in 1833 (No. 7901X). Nothing survives of those patents except their titles -- both were destroyed in the Great Patent Office Fire of 1836 -- but they are consistent with his later career as a mechanically-minded skilled carpenter and pattern maker.

When Ripley lived there, the small community of Schenectady inventors was dominated by one man, the Reverend Dr Eliphalet Nott, president of Union College and the most prolific and influential stove inventor in the country at the time. Nott took out twenty-four patents between 1826 and the 1836 Fire, almost all of them for stoves designed to burn anthracite, the new wonder fuel. Seven men including Ripley took out the other eight. This can only be speculation, but it seems reasonable to imagine that Ripley may have assisted the local builder Joseph Horsfall and carpenter Nicholas A. Vedder in designing and making the patterns for Nott's stoves, or at least have become familiar with them.

Nott's stoves were made under the management of Horsfall and Nott's sons Howard and Benjamin at the Union Furnace in Albany, probably the largest stove producer in the Capital District at that time, and that was where Ripley's first stove patent was taken out in January 1836 (No. 9341X). It too was destroyed in the Great Fire later that year, so that only the short version of its name -- "Stove-Pipe" survives.

What might it have been? A clue comes from two of the three other 1830s patents using the same term, both of them Nott's work [patents 7639X and 7643X, June 1833]. The two records seem to have been mixed up by the Patent Office, with the drawing for the one accompanying the text of the other. If we unscramble them, we find that Nott's "Stove-Pipe" was a fundamental change in the way these were usually constructed at the time. His "improvements made in the material, form and construction of stove pipe to be employed, where anthracite coal is the fuel in use" were designed to solve the problem of the "great inconvenience [that] has arisen in the use of anthracite coal, from the escape of gas" from regular sheet-iron flues connected with fabricated "elbows." Nott's solution, "tested and perfected by repeated experiments," was to replace sheet-iron flues by hollow cast-iron sections for the hottest parts of the flue system immediately above the fire, designed to transfer heat from the flue gas into the room the stove was intended to warm. Flue gas would only flow into fabricated wrought-iron pipes once it had cooled down somewhat and was close to exiting the room.

Nott's elaborate, decorative flues were built up from cast sections jointed, screwed and bolted together. Smoke-tightness depended on making precise, quite thick and heavy castings not liable to be distorted too much by heating and cooling. These entirely functional structures "may present any external form though some regular architectural form is preferred." In the accompanying illustration an essentially baroque revival style was chosen, but six years later a mixture of classical and gothic was used [Nott's "Magazine Stove," Patent 1260, July 1839]. It seems clear that what Nott was doing was inventing, or at least formalizing, a new decorative heating stove type -- the columnar stove, which became a Capital District specialty from the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s. (See this blog post from 2013 and, for Nott, this one from 2015).

|

| Nott's stove pipe was basically a hollow flat box, with most of the decoration raised on the surface, corners precisely jointed, and all held together by rods and bolts in usual box stove style. |

|

| Nott's final (1839) stove patent shows his 1833 stove pipe on an essentially Gothic stove, framed by classical columns which served as additional heat exchangers. |

My guess is that Ripley's lost 1836 patent might have been for an improvement in the design and manufacture of the hollow column flues that were such key functional and decorative features of what was rapidly becoming one of Albany and Troy's most popular stove types, perhaps by casting them in one piece. This would have eliminated the leaky joints that were in practice a feature of those whose flues were, like Nott's, fabricated from several cast plates. The best collection of descriptions and images of these stoves is in Tammis K. Groft's Cast With Style: Nineteenth-Century Cast-Iron Stoves from the Albany Area (Albany: Albany Institute of History & Art, 1981, rev'd ed. 1984), pp. 46-62; see also my old blog post. Most of them appear to feature one-piece flues -- quite achievable with skilled design and coremaking of the sort Ripley perfected (see his 1846 tea-kettle patent, below).

My supposition -- and it can be nothing more than that, without more evidence -- is that Ripley probably worked for the Nott brothers at the Union Furnace, and after the Notts lost control of it in the financial crisis of the mid-1830s he had to strike out on his own as a stove pattern maker, building on the experience he had acquired there. Ripley probably honed his techniques as the designer and patternmaker responsible for creating some of the fine columnar stoves now recognized as masterpieces of the stovemaker's art. Unfortunately we will never know because there are no surviving records from Capital District firms stretching back that far, as well as no design patents (only introduced in 1842), so all we can be sure of about these stoves is the names of the companies that made them, and sometimes not even that. Many of them were Ripley's later clients, which makes it reasonable to suggest that he may have been involved with them earlier too. Some time between 1836 and 1843 he moved ten miles north to Troy, whose own stove manufacturing industry was already big enough to have supported the first dedicated stove pattern shop in the district since its establishment by Samuel Hanley in 1830. (Ripley's obituary in 1873 said that he had lived in Troy for more than 40 years, but without census or directory evidence -- he was not in 1829's -- and in the absence of earlier mentions in the local press, we cannot tell whether this is correct.)

What about Ripley's future partner? How did his path lead him to Troy? Nicholas A. Vedder, one of Nott's original pattern makers, was still living in Schenectady in 1841 and working as a carpenter like four more of the other fifteen adult male Vedders in the local directory for that year. But Nicholas S. (b. 1819), his cousin, began his apprenticeship not with him but in 1831 in Troy, probably with Hanley, as a boy of 12. He had lost his father when he was four years old, and needed a start in life. According to a biographical sketch written shortly after his death in 1879 by one of his own old apprentices, Nicholas embarked on this career "through the influence and advice of Dr Nott." Presumably his cousin introduced them. [Joseph L. Gobeille, "Engineering and Mechanical Problems in Cook's Stove Construction," Jnl. of the Association of Engineering Societies 5 (1885): 204-13 at 205.]

By the mid-1840s young Vedder had acquired enough experience and capital to buy and expand Hanley's pattern shop -- but did he do this by himself though just in his mid-twenties, or was it in association with Ripley, then almost 50? A search of the local press has cast no light on this question, and local directories are also unavailable online until 1857's, so the lines joining up the observed dots in these men's lives and careers can only be drawn in pencil at this stage. Vedder later claimed to have founded his Pattern Works in 1835, but this may simply have been when he completed his apprenticeship.

* * *

Ripley's career was the one that left the most marks in the public record for the next several years. In 1843 he was advertising to local clients "a new process for 'manufacturing patterns for casting' that would allow for even bolder configurations and ornamentation." [Groft, p. 46.] And he took out another stove patent, the first of a steady stream over the next dozen years, which showcased his skills.

His "Stove-Column" (Design Patent 5) "possesses no advantage over the ordinary column now in use except in beauty of appearance." It was cast in one piece including the base, the shaft, and the capital, which had become the norm. The patent was assigned to a Troy firm that specialized in producing parlor stoves of this type -- Elias Johnson, Gilbert Geer, and David B. Cox; its members had entered the local stove trade between 1834 and 1841, and would remain active within it until the 1860s. Another Geer, Erastus, was one of the witnesses, which makes it even more likely that Ripley was working to a commission in this case.

This patent of Ripley's was innovative in a different sense than laying any claim to technical improvement: he was the first stove designer to take advantage of the new type of patent -- cheaper ($15 rather than $30) and easier to get than an invention patent -- enabling them to secure an intellectual property right in the external appearance of stoves. This encouraged competition among designers and makers on the basis of their products' beauty as decorative home furnishings rather than simply or at least principally as objects of practical utility. Where Ripley led, everybody else followed, and for the next couple of decades most design patents were for stoves, and most stove patents were for designs. And more of them were from the New York Capital District than from anywhere else. [See my 2009 Winterthur Portfolio article, esp. pp. 375-381.]

|

| Ripley's "Dolphin" Stove Column, Design Patent No. 5. |

|

| Note the patent date -- the 1842 Design Patent law required products to carry this information. |

Over the next dozen years Ripley took out another twenty-six stove design patents. These probably represented just a fraction of his pattern-making work -- what he or the company commissioning him thought likely to be their most marketable products, which would therefore be most likely to attract imitation and so were most worth trying to protect. Not all of them are worth illustrating here, mostly because the quality of online images in the US Patent Office records is quite variable. But here are the basic facts about them:

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Cox, Abram & Gale, Ansel H.

Assigned to: JOHNSON, GEER, & COX [Troy]

Very floral [including "a bunch of melons & grapes"] -- p. 2 "to be used in the manufacture of air tight or other box stoves" -- p. 3 "It is impossible to describe accurately in language the ornamental carvings on the surface of the plates but the same is represented as accurately as possible in the side plate of the Engraving or drawing hereto annexed and by the pattern or model herewith transmitted."

Design patents were quite often only for one or some of the plates of a stove, like this one -- the most heavily decorated, not all. Pattern makers working from them could modify or extend a design to suit the dimensions and other requirements of a particular plate, whether front, back or sides. Ripley's language about the limitations of a design patent's descriptive text followed a formula adopted by most designers, which emphasized that the drawing (and/or the prototype castings sometimes submitted with it) contained the crucial evidence for their claim.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Atwood, Anson & Adancourt, F.

Assigned to: F. JAGGER, TREADWELL, & PERRY [Albany]

Square parlor heater, rococo (?) style, covered with fruits and foliage. The drawing, at least as reproduced here, seems very loose and lacking in detail -- e.g. the cross-hatching on the hearth. A pattern maker could not work from a drawing like this.

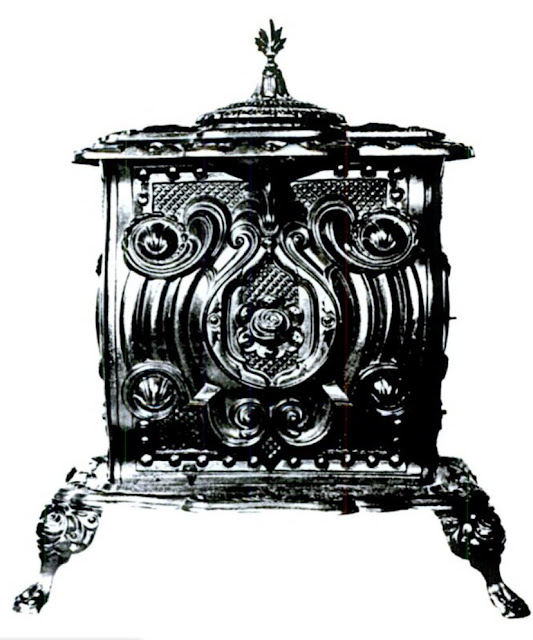

We can see much more of the detail in this picture of the rather splendid finished product -- essentially a quite conventional wood-burning airtight stove with a fuel feed door on the right, but with a grandiose, bulging shape and every inch of its surface decorated. The original illustration in Groft's book, of which this is just a screengrab from Google Books, makes clear why Design Patent 32 is so lacking in detail: that was all in number 25, taken out eight months earlier. Note that the maker's date on this stove is 1844, the same as number 25. I have no idea why Ripley took out two patents for the same stove in this peculiar fashion, but note that the second was assigned to a different (Albany) firm.

|

| Johnson, Geer & Cox, Troy, NY, Parlor Stove, 1844, 47.5" x 33" x 23" from Groft, Cast With Style, p. 64. |

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Sheldon, C.D. & Geer, Erastus (note that there is a different witness on the drawing -- Wm. Johnson. This is quite common.)

Assigned to: JOHNSON, GEER, & COX

p. 2 For an "airtight or box stove." This time Ripley submitted designs for the top and front; the back and sides would have been versions of the front plate, modified to accommodate doors and a smoke flue collar. He uses the same "impossible to describe" language but makes no reference to submitting a model, suggesting that he, other design patentees, and the Patent Office itself were getting used to the differences between them and invention/improvement patents. The top was covered with "elevated & depressed" carvings (i.e. relief and incised patterns -- unlike some patentees, Ripley did not know the formal terminology of sculpture) consisting of "Rosetts (sic), scrolls, Diamonds, leafs and other fancy carvings." As for the sides, "The carvings on the surface are designed to represent the front of a Gothic Cottage, with two large Gothic windows ... surrounded by Gothic mouldings interspersed with Rosetts & beads..."

|

| "Gothic Air-Tight Parlor Stove," Johnson, Geer & Cox/Geer & Bosworth, Troy, NY, 31" x 29" x 19.5", from Groft, Cast With Style, p. 67. |

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Adancourt, C.L. & Adancourt, F.

Assigned to: LOW, CHOLLER (), & JONES

A parlor heater -- another fairly crude drawing of a stove "The interior of which is one entire space for fuel." A pattern maker could not produce the plates for this stove, with its complex, bulging shape and overall surface decoration, from such a drawing; but, unlike in the cases of patents 25 and 32, above, there is no separate detailed patent for the decorative scheme.

Here, too, the stove itself gives a far better impression of the design than the unusually inadequate drawing.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Browne, A.P. & Greenough, J.J. DRAWING says Keller and Greenough agency

No Assignment data with the patent, but surviving stoves are by Johnson & Cox.

'Gothic' pattern -- "the upper part of the side of which is formed of quatre foil in circular recesses as shown in the drawing at (a). On each side near each corner are three compartments (b) of trelliswork in imitation of three windows one above the other, and in the centre between them is a large door shaped compartment (c) divided into two vertically by scrollwork (d) flanked by gothic pendules (e); on each side the ground work between the bars is all formed in diamondwork all of which will more clearly appear by the drawing accompanying this description in fig. 2.

The top of the design is oblong having a square compartment (f) in the centre with indented corners at each end of which is another compartment (g) ornamented with line and leafwork; and on each side are compartments (h) formed of leaf ornament these compartments project beyond the line of the stove as shown in the drawing, the corners are filled with a honeysuckle pattern and the space between them is occupied with a quatre foil (i) in a die."

The drawings in this case were quite detailed. This is perhaps because they were made for the Keller & Greenough patent agency, i.e. Ripley was becoming sufficiently experienced, and the process of securing a design patent more formalized, that professional patent agents were emerging and Ripley was using their services rather than just local attorneys or his own efforts. This may also explain the thorough and systematic description.

Pictures of rusty and cleaned versions of the stove plates produced from Ripley's patterns show the quality of fine castings Capital District foundries could produce by the mid-1840s, which both responded to and helped drive the demand for elaborate surface decoration and increasingly difficult shapes like Design Patent 43's.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Browne, A.P. & Dysert, William

No assignment data, but given that this was produced at the same time as No. 73 and was so similar, including in its stylistic ambitions, it seems reasonable to think that it may also have been for Johnson & Cox, Ripley's most frequent customers.

Gothic design for front (or back) & side plates: "This design is intended to be cast in metal in bold relief and is composed of gothic ornaments having a bold foliated cornice (a) below which the side is divided into three compartments (b, c, b) by perpendicular pendules (d) which terminate in points above the bottom and under which there is a projecting plain moulding (e). The centre compartment (c) is deeply recessed and the ground work is diamond or cross barred. The end is similar in its combination of raised and scroll work &c to the centre compartment as is fully delineated in fig. 1."

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Boughton, A.M. & Cox, Joseph

Assigned to: JOHNSON & COX

Another single-plate design of (p. 2) "a bold, fancy figure" -- geometrical, and described in detail in the accompanying text.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Stewart, Saml. & Harvey, Samuel

Assigned to: JOHNSON & COX

p. 2 Parlor stove "of bold configuration" -- "an ornamental bracket of an entire fancy device" -- "bold fancy scroll, leaf & diamond work" -- front and side plates.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Henry, Ch. & Farling, Wm. H. Jr.

Assigned to: JOHNSON & COX

Gothic pattern for the front of an air-tight stove -- p. 2 "an ornamental vase piled up with leaves, flowers & buds."

The record includes the same image as in the one for the following patent, which the description for this one does not fit. This must have been an error with the original filing.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Henry, Ch. & Farling, Wm. H. Jr.

Assigned to: JOHNSON & COX

Design for Parlor Stoves; (a copy of the?) original drawing is available at Rensselaer County Historical Society.

The design was (p. 2) "of a bold configuration and is ornamented with leaves, mouldings, Diamond, and Gothic work." It included a "Gothic niche with diamond back ground & a fancy dome." Most unusually Ripley included some dimensions -- the horizontal cylinder "occupies nearly one third of the plate commencing about five inches from the bottom and extending upward about eighteen inches."

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Ingalls, H.B. & Fuller, J.E.

Assigned to: JOHNSON & COX

Front and side (end) plates of a parlor stove (p. 2) "of a bold configuration and finished near either edge with bracket carved work." A feature of the front plate was the mica panels -- the narrow vertical slits pointed at both ends in the plate on the right -- allowing a view of the fire.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Fuller, Jacob E. & Ring, George W.

Assigned to: COX & Co., Abram

Plates for an air-tight Gothic parlor stove. The front was decorated in checker pattern -- (p. 2) "a bold piece of carved work"; the top included two boiler holes rather than the usual one, which would have made the stove more useful for light cooking. The text makes no reference to this functional feature, just to the decoration.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Fuller, Jacob E. & Ring, George W.

Assigned to: COX & Co., Abram

Shows front and top plates for parlor stove, as with 180 above. The front included "four bracket pilasters..., also three Gothic niches ... with diamond ground work"; the top plate was "in carved work of a fancy device covering nearly its entire surface."

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Fuller, Jacob E. & Cox, Abram

Assigned to: JOHNSON & COX

Front plate for the "American Cottage Air Tight" Parlor Stove, partly Gothic in style.

[no picture -- missing]

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Fuller, Jacob E. & Cox, Abram

Assigned to: JOHNSON & COX

Front plate for "American Cottage Air Tight" Parlor Stove -- text seems to be identical to 193's, and refers to four figures, only one of which survives with the USPTO archive copy.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

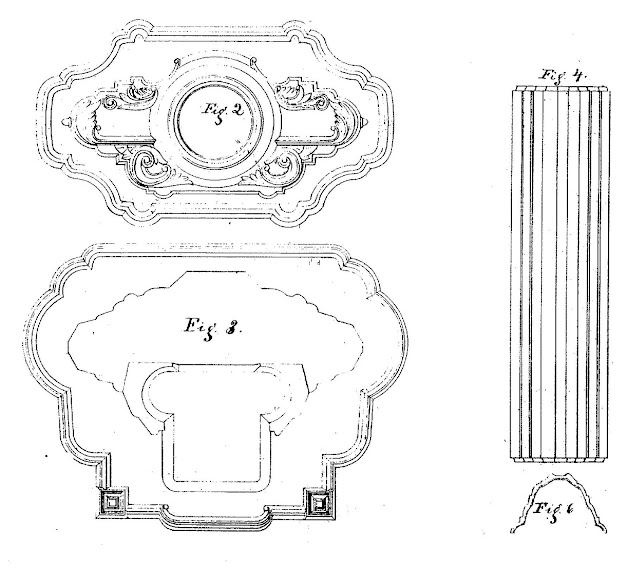

Witnesses: Ware, C.L. & Brundage, E.L.

Assigned to: EDDY, George W. (Waterford, NY)

Parlor Stove -- thoroughly illustrated with six separate drawings of the front, top, hearth-plate, rounded ends (Fig. 4) and profiles through the front (Fig. 5) and end (Fig. 6) plates, showing their complex outlines. These drawings were not the work of a pattern shop like Ripley's but of a professional draughtsman, E.L. Brundage of Troy, who also served as one of the witnesses. This design is very different from Ripley's earlier style of "Carpenter Gothic" -- it is much plainer and more furniture-like. This patent marked the start of a fashion in the 1850s for making stoves look like something different.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Ware, C.L. & Brundage, E.L.

Assigned to: EDDY, George W.

(p. 3) "The distinguishing feature ... is a representation of a town clock face combined with ornaments & mouldings." This is clearly the companion design to 327, except that in this one Brundage describes himself as an "Agent of Patents."

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Brundage, E.L. & Bell, E.

Assigned to: STAFFORD & Co.

(p. 3) "a parlor stove which I call the Regulator" covered with "arabesque figures." "The ornament is only represented in part, the blank part of the plate having the same ornament as that represented" -- this was a way of economizing on drawing-office work where a pattern was symmetrical or included repeating patterns.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Brundage, E.L. & Bell, E.

High-quality image of a smart parlor heater -- p. 3 "which I call the Grecian parlour" -- covered with the usual "rosets (sic) & arabesques." There is nothing particularly "Grecian" about the design. Note that the draughtsman has omitted the front left stove leg. This is not an "airtight" stove, more of a "Franklin" permitting a good view of the anthracite fire through one or other of the pairs of (sliding) doors.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Brundage, E.L. & Hyde, H.J.

Assigned to: CHOLLAR, GAGE & DUNHAM [W. Troy]

Cooking stove "Boston Casket Patented 1851" -- p. 3 the decoration includes all of the usual "roseats...bead mouldings... [and] arabesques" from the wood carver's pattern-book repertoire. The stove was a standard large-oven "square cook," with four boiler holes. As cooking stoves matured as an appliance type and became increasingly similar to one another in structure and function, designers and makers attempted to distinguish them from one another by brand name (which often said something about the intended market -- in this case, New England) and external appearance. Working by himself, Ripley had stuck thus far to designing parlor stoves. In partnership with Vedder he began to produce more decorated cook stoves too -- a much larger market. The cook stove was the bread and butter of every stove maker's output, and every stove retailer's display and sales.

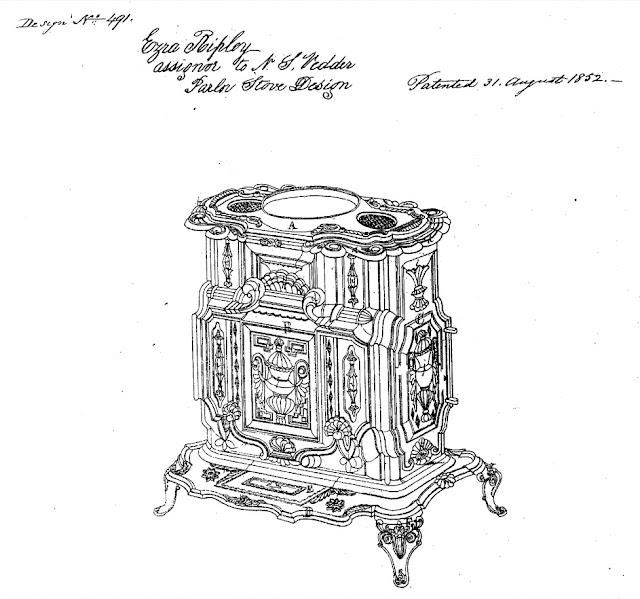

Ripley, Ezra & Vedder, Nicholas S., Troy, NY

Witnesses: Brundage, E.L. & Snyder, A.

Assigned to: LOW & HICKS

See above, at start of this post. A gothic parlor heater (p. 2) "which we call the severe air tight," with Gothic arches and a diamond pattern.

Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Savage, John J. & Savage, E.W.M.

Assigned to: VEDDER, Nicholas S.

A rather nice airtight wood stove, i.e. a typical Troy product, heavily decorated with Ripley's usual elaborate, deeply carved surface and complex design of scrolls, scollops, diamonds, etc. Ripley called this the "Kossuth Parlor" -- after Louis/Lajos Kossuth, Governor-President of the Kingdom of Hungary during the revolution of 1848-49 who had become a hero and celebrity in the United States during his tour in 1852, which included a parade and reception in Troy i.e. the stove was named when Kossuth was on everybody's lips, to help make it more distinctive, memorable, and attractive. ["Kossuthiana," Troy Daily Whig 27 May 1852, p. 0506.]

Vedder was the assignee of this design, which was unusual at the time as he was not a maker in his own right. But his business model would be different from Ripley's. Rather than working, usually, on commissions, Vedder began to produce speculative designs and made his money by selling the rights to use them to several different makers, who could apply their own company and brand names to the stove designs he sold them. This enabled him to extend his market, and his influence on stove design, far beyond the Capital District itself. As his own company grew, he added to the services he offered customers -- not just designs on paper or wood patterns, but hard-wearing iron patterns that they could use in volume production. In 1852 most of that was in the future, but Vedder was already prepared to commission a design from his colleague Ripley and take on the marketing of it himself.

Ripley, Ezra D. & Vedder, Nicholas S., Troy, NY

Witnesses: Savage, John J. & Johnston, Thos.

Assigned to: McCLURE, Samuel [Rochester, NY]

The Peach Branch Air Tight cook stove, with door ornamentation of peach branches. Note that the top plate of the stove is left blank in the design. It was purely functional and the layout was entirely standardized.

Ripley, Ezra & Vedder, Nicholas S., Troy, NY

Witnesses: Savage, John J. & Moran, John

Assigned to: EDDY, George W.

One of the most extraordinary looking parlor stoves I have ever seen, which I always thought of as the "rocket" stove until I found that its designers called it the "Castle." In layout and function it was an entirely conventional airtight heating stove. The peculiar shape had no practical purpose, and would certainly have made it harder to keep clean. This became a collector's item, and figured in Tammis K. Groft's classic Cast With Style exhibition at the Albany Institute and other venues, 1980-1986, which marked and sparked the modern revival of interest in these objects. She borrowed a "Castle" from the great collection of John I. Mesick of Schodack, NY, and included a wonderful picture of it on p. 71 of her exhibition catalogue.

|

| Advertisement in Mohawk & Hudson Foundry, Catalogue and Illustrated Views of Stoves Manufactured by G.W. Eddy (Troy, NY, 1854), p. 11. |

Ripley, Ezra & Vedder, Nicholas S., Troy, NY

Witnesses: Bell, E. & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: JOHNSON, COX, LASKY & Co.

Another square cook "which we call the 'Empire-City" (p. 2), this time showing the detailed arrangement of the top plate (the four round boiler holes could be reconfigured as two oval holes, for different sorts of cooking; this was entirely usual) and also, via a cutaway, the construction of the box hearth.

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY (the drawing still reads Ripley & Vedder)

Witnesses: Savage, John J. & Bell, E.

Assigned to: FILLEY, G.F. [Giles; St Louis, MO].

Giles Filley (see this blog post from 2015) was the proprietor of the relatively new Excelsior Stove Works. He was a Yankee migrant, and looked back East for the skilled workers, raw materials, and high-quality designs to enable his factory at the far western edge of the U.S. manufacturing belt to compete with goods from established east-coast manufacturers. His older brother Marcus Lucius remained in Troy, where he was a lawyer, and served as Giles's agent. But he was so impressed by Giles's rapid success that in 1854 he and a cousin, Lucius Newberry, joined together to buy an established stove maker (Morrison & Manning) and enter the business themselves. Though Giles bought the right to the "Magnolia" patent, his older brother and cousin may have participated in the deal. They certainly made "Magnolias" at their Green Island foundry themselves. The "Magnolia" was an attractive parlor stove, decorated with the usual scrolls, roses, diamond work, checkered work, etc. Its bold, swirling front plate and overall proportions worked much better than e.g. D32's and D43's a decade earlier.

|

| "Magnolia" Stove by Newberry, Filley & Co., Troy, 37.75" x 32.25" x 19.5", from Groft, Cast With Style, p. 69. |

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Savage, John J. & Moran, John

Assigned to: COX, RICHARDSON & BOYNTON [Troy]

The "Peyton Air Tight" -- a four-boiler "square stove" with a sort of marquetry design.

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Moran, John & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: SWETLAND & LITTLE [Crescent, NY]

A heavily-moulded, bulging box stove, with a rosette on the side panel -- called the "Forest Rose," but actually quite similar to the "Magnolia."

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Moran, John & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: POTTER & Co., L. [Troy]

Front plate of a parlor stove. The Patent Office changed its practice, to reduce the burden on applicants and also to minimize the number of large-scale drawings and even models or iron plates that it had to file, by permitting them to be replaced by photographs of actual plates. The quality of these, as reproduced in the online record, is usually not worth reproducing. But the small image available does enable us to see that the design is the usual mix of plumes, scrolls, and checker-work, assembled into a quasi-heraldic coat of arms.

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Ball, M. & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: POTTER, Louis [Troy]

A complementary design -- the front plate for the "Tropic" box stove (probably a reference to the amount of heat it would produce), composed of a pineapple, scrolls, and leaves. Again, just one plate is shown; the other sides would have been variations of it. Another small photographic reproduction.

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Moran, John & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: VEDDER, Nicholas S. [self]

Another box stove, but this time the side and open fire door are shown in the photograph. The decoration was decidedly martial, including a "shield... tomahawk... ensigns... cannon... cannon balls... drums, rifles or muskets... swords...& other implements of war."

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: McArdle, George & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: POTTER & Co.

Another poor but serviceable photograph of the side plate of a box stove, with a "large symmetrical ornament" of scrolls, leaves etc.

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Sanderson, Wm. L. & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: POTTER & Co.

A better small photo just about worth including as a representative of these late-1850s designs. This was for a box stove.

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Stone, L. & Savage, John J.

Assigned to: VEDDER, Nicholas S. [self]

A poor-quality engraving of a quite plain six-plate [box] stove. An interesting question, to which I have no answer, concerns the change in Vedder & Ripley's practice -- why all of these patented designs for so many very generic, low-value products? Box stoves were some of the cheapest items in a stove maker's range -- from $2 to $4 for standard sizes, less than half the price of parlor stoves. Why invest so much effort at the bottom end of the market?

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Winslow, E.S. & Park, Austin L.

Assigned to: VEDDER [self]

At last, something interesting. This was another box stove, but a singularly novel and attractive one -- the "Cushion" stove, a novelty product with its surface made to look like upholstery. (Why? I have not the foggiest idea. But mid-19th century stove designers thought that, for example, a heating stove in the shape of an elephant, or a parlor stove made to look like a Second Empire mansion, with doors, windows, and a mansard roof, was worth making and selling. It would certainly stand out in a crowded marketplace.) Even the photographs illustrating the patent do quite a good job.

Vedder, Nicholas S. & Ripley, Ezra, Troy, NY

Witnesses: Stone, Lucius & Park, Austin F.

Assigned to: VEDDER [self]

Another cushion stove, which suggests that the first one sold well. This time they only submitted a photo of a single side-plate which looks squarer and flatter than the first, and had a different sort of upholstery pattern of bands and rosettes.

Why after almost twenty years did Ezra Ripley retreat from being a leading figure in the stove design and pattern-making business, and only carry on as second fiddle to his younger partner for another nine? We can only speculate, but Ripley's career as an inventor was already at least a decade old before he began to concentrate on the stove industry, and he maintained parallel interests in other fields right through his busiest period as a stove designer. It just seems that these became more important and, probably, more remunerative for him. The way he described himself in the Troy directories and 1865 New York State census reflects this: as "designer and inventor," and eventually just "inventor." When he died, the Troy Daily Whig commemorated him as an "inventor of considerable prominence" and "great celebrity." His inventions were "used in all parts of the country, but more particularly by the stove men, who have profited much by his scientific advice." [19 June 1873, p. 0591, 20 June 1873, p. 0596.]

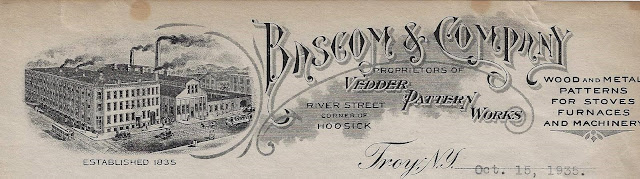

Vedder, on the other hand, specialized in stove design quite early and never abandoned this focus, describing himself in 1865 as simply the "head carver" in his business, and still working at the tools, while becoming the "prince of stove designers . . . to whom we owe the greater part of our modern conveniences in the cooking stove, either as absolute inventor or else the man who worked out the idea and made it practical." He became the largest and most influential in the country, with a nationwide market. Vedder took out 121 stove design patents, 1851-1870, plus another dozen as second-named patentee, only three of them not with Ripley -- about a tenth of the national total; by the early 1870s that proportion had risen to about a fifth. This single-minded attention to one business made him a rich man: his estate at his death in 1879 was worth about $140,000 (c. $40 million in 2019 dollars), $2,500 of which was spent by his widow on a huge granite monument in Troy's Oakwood Cemetery. $30,000 of this was the value of his Pattern Works, a comparatively large enterprise (125 employees in 1895) continued by his former bookkeeper Henry Clay Bascom and his successors until at least 1935.

|

| The Vedder Pattern Works in 1895, from Citizens' Association of Troy, Industrial Advantages of Troy, N.Y., and Environs (Rochester: James P. McKinney, 1895), p. 51. |

Meanwhile Ripley diversified, eventually finding one winning product type (the humble tea-kettle) on which to concentrate his attentions. I am not going to give as much space to this other part of Ripley's career, but as I know that some of the people who stumble across this blog post may also be collectors of old tools, kitchen equipment, etc., a classified list of his other patents will illustrate the breadth of his interests and link readers to the patents they generated.

Improved Foundry Techniques:

Casting hollow ware, &c., Method of making patterns for / Pat. Num. 3,724 1844 -- making iron patterns for casting (stove) plates and hollow ware from wood originals ("block patterns") using a plaster of paris intermediate stage. This became one of the fundamental pattern-making techniques of the volume-production foundry, so it's appropriate that the witnesses were stove makers Abram Cox and Erastus Geer. There is no illustration with this patent, simply a technical description. Patents for foundry methods improvements were very rare in the 1840s and 1850s; it was still a craft with almost no formal systems of instruction or experience-sharing.

Tea-kettle / Pat. Num. 4,417 -- 1846 -- a cored pattern for a thin-walled kettle, which could be made in a simple two-part mold without a complicated core to make the spout. The result would be easier and cheaper to make and superior in operation to one of conventional pattern. Witnesses A.P. Browne and J.J. Greenough.

Rasps, files, &c., Chill for casting / Pat. Num. 6,510 -- 1849 -- the advantage of Ripley's "chill" (a partly metallic mold, producing rapid solidification and surface hardening of the resulting casting) was that it enabled the manufacture of unprecedently sharp rasps and files, hand tools for which there was a huge demand. Witnesses E.L. Brundage and E.D. Parke.

Casting metal / Pat. Num. 14,115 -- 1856 -- a simple mechanical appliance assisting the molder in making small metallic castings with sharp edges, points, or lines, cheaper, e.g. paper and letter seals, ornaments, small gears, and hardware. Witnesses J.J. Savage and John Moran.

Grinders, Method of forming teeth upon cast-iron / Pat. Num. 8,293 -- 1851 -- Ripley's file- and rasp-making patent of 1849 was largely designed to meet the needs of the large milling industry for tools for making and maintaining mill-stones. Two years later he was adapting his skill in casting sharp metal teeth in chills to the production of iron substitutes for millstones. Witnesses Wm. L. Leamed (Learned?) and W.S. Hevenor, i.e. men not involved with any of his other patents, indicating that he was reaching outside of the Troy stove-making community.

Grinding-mill for grain / Pat. Num. 13,996 -- 1855 -- hand-cranked, with adjustable cast-iron grinding gear, for anything from coffee to animal feed, corn or wheat meal. Witnesses Nicholas S. Vedder, John J. Savage -- i.e. his usual partners in stove design and pattern-making.

Grinding-mill / Pat. Num. 17,116 -- 1857 -- similar to the above, but with grinding gear of vertical rotating plates rather than cylinders or cones. Witnesses John J. Savage, R.A. Gottridge.

Hand Tools:

Wrench / Pat. Num. 16,997 -- 1857 -- adjustable wrench for square nuts and bolts -- cheap, efficient, and durable; made of just two pieces of cast iron, rapidly assembled and requiring no finishing. Witnesses Ed. H. Uniac, Austin F. Park.

Wrench / Pat. Num. 30,987 -- 1860 -- adjustable wrench with a different (sliding rather than hinged or ratchet) handle, and square jaws. Witnesses L. Stone, J.J. Savage.

Wrench / Pat. Num. 31,034 -- 1861 -- adjustable pipe or round bolt wrench. Witnesses L. Stone, J.J. Savage

Tool-holder / Pat. Num. 93,906 --1869 -- a tool-handle (combining a stock and light hammer), designed for simplicity, cheapness, convenience, and durability in manufacture and use. Witnesses Geo. S. Prindle, Edm. F. Brown.

Hardware:

Faucet / Pat. Num. 10,641 -- 1854 -- a Molasses Gate -- a special sort of barrel spigot, commercial rather than domestic use? Witnesses J.J. Savage, John Moran.

Faucet, Balance-gate / Pat. Num. 12,830 -- 1855 -- another complicated, specialized tap. Witnesses A.A. Lee, J.J. Savage.

Kitchen Equipment and Hollow Ware:

Nut-cracker / Pat. Num. 24,238 -- 1859 -- Bench-mounted, lever-operated; parts simple to cast, without cores, and easily assembled. No noise, no shock to the user, no risk of pinched fingers. Witnesses George Macardle, Austin F. Park.

Hollow-ware, Mode of hanging covers to baled metallic / Pat. Num. 31,035 -- 1861 -- this was probably Ripley's most important patent, in terms of its value to him at least. It was a redesign of the tea-kettle so that the lid didn't fall off when it was tilted to pour. The body of the kettle was simple and elegant in shape, probably made in a two-part mold with a curvaceous parting line. Witnesses to the original patent: John J. Savage and Nicholas S. Vedder, i.e. his usual collaborators in stove pattern making.

It is often impossible to know whether a patent led to the production of a marketable product, and turned into a worthwhile investment of creative effort, or not. The best evidence of this, apart from inventor and company records (if any survive), original case records of the US Patent Office, mentions in the contemporary press, and survival of artifacts themselves, is what's called "patent management" -- the legal record of a patentee's (or assignee's) efforts to make money out of it by selling it to others, extending a patent's validity, defending it in court, etc. Ripley's tea-kettle patent was worth enough to him and/or his assignees for him to reissue it twice, in 1865 and 1869, which gave him the opportunity to clarify his claims of originality and strengthen them against possible imitators. None of his other patents deserved or received this treatment.

Ripley's concentration on perfecting and exploiting his most marketable idea in the 1860s probably explains why he finally gave up the art of stove design.

Tea-kettle / Pat. Num. RE 2,122 -- 1861, 1865 -- witnesses Charles D. Kellum, B. Macgregor.

Tea-kettle / Pat. Num. RE 3,256 -- 1861, 1869 -- witnesses R.T. Campbell, J.N. Campbell.

Tea-kettle / Pat. Num. RE 3,256 -- 1861, 1869 -- witnesses R.T. Campbell, J.N. Campbell.

Tea-kettle / Pat. Num. RE 3,257 -- 1861, 1869 -- ditto (the 1869 Reissue was so extensive that it was split into two separate applications).

Culinary vessel / Pat. Num. 41,095 -- 1864 -- a new design of handle for tea-kettles and saucepans. Witnesses Nicholas S. Vedder, Austin F. Park.

Tea-kettle covers, Hinging / Pat. Num. 66,631 -- 1867 -- a kettle with a bailed handle and slide-off lid, pivoting at the side rather than the rear. Witnesses Leslie Smith, Austin F. Park.

Tea-kettle / Pat. Num. 79,860 -- 1868 -- uses a flat lid as a warming tray for plate of cakes or coffee pot when there is no room on the top of the stove. The patent was assigned to Ripley himself & W.C. Davis, a large Cincinnati manufacturer, i.e. this was not a mere "paper patent," it had already found a market. Witnesses Geo. H. Knight, Austin F. Park.

Screw-handle attachment / Pat. Num. 81,111 -- 1868 -- For dippers, saucepans, and long serving spoons. Witnesses Chas. D. Kellum, William Faly (Fahy?)

Newspapers, music, &c., Ready-binder for / Pat. Num. 536 -- 1837 -- a simple, handy device made of spring-steel and wood. Witnesses A. Thomas, Geo. I. Bloomendale.

Stands, Construction of base for / Pat. Num. 7,291 -- 1850 -- bases of metal stands for tables, chairs, music-stools, etc. Could be sold as-cast, easily assembled. Witnesses E.L. Brundage, John L. Davy (a Troy foundry operator, so perhaps a customer?).

Button-fastener / Pat. Num. 80,224 -- 1868 -- a quick, cheap, simple, and detachable device, made of leather. Witnesses Chas. D. Kellum, William Fahy. What was a wood pattern-maker and designer of things made out of iron doing inventing something like this? Just attempting, probably unsuccessfully, to monetize what he thought of as a bright idea. Troy did have a substantial clothing industry, though, so it's possible that he thought there would be a local customer.

Toy-pistol / Pat. Num. 83,211 -- 1868 -- a spring-powered pistol. Witnesses George Macardle, Austin F. Park.

Other Complex Metal Products:

Car-seat / Pat. Num. 8,508 -- 1851 -- Jointly with E. Booth. Reversible high-back (night) car seats, for street and mainline railroad carriages, so that they could be moved to face the right way at the end of a run. Witnesses E. L. Brundage, A. Snyder. Troy and Albany had railroad car builders, but I do not know if these seats entered production.

Car-seat / Pat. Num. 8,583 -- 1851 -- almost identical except with E.L. Brundage instead, and a month later. Witnesses E. Bell, Giles B. Kellogg.

Gun battery, Repeating / Pat. Num. 33,544 -- 1861 -- probably Ripley's greatest claim to fame, though it may never have been built. A predecessor to the Gatling Gun, and a year earlier. Witnesses A.L. Winne, Geo. F. Ells.

I like it!

ReplyDeleteWow! Troy is my home town!

ReplyDeleteLucky man! Lots of good old stoves to look at there in the Rensselaer County Historical Society. Beautiful design patent drawings too.

ReplyDelete